Tread Carefully: Ontario’s cap-and-trade system meets a fork in the road

Ontario elected a new government yesterday, and as far as carbon pricing is concerned, change is afoot. The province’s cap-and-trade system is working well, but the incoming Progressive Conservatives have signaled their discontent with the status quo. In this blog, we’ll look at their options—everything from leaving the WCI entirely to changing how auction revenues are spent.

If it ain’t broke…

Ontario’s cap-and-trade system has been working successfully for 18 months. Under cap-and-trade, businesses buy from a limited supply of permits to produce carbon emissions. They then buy and sell these permits amongst themselves to ensure they have enough to cover their emissions. Firms can either reduce emissions or buy additional permits, whichever is cheaper for them. Overall, this reduces GHG emissions by the required amount and at the lowest possible cost.

Ontario’s system is linked with California and Quebec’s under the Western Climate Initiative (WCI). Linking in this way helps keep costs low. The WCI system is well-designed and on a solid footing—legal uncertainty surrounding the program in California is resolved, and after a glut of permits had been keeping auction prices stubbornly at the floor, stabilization mechanisms kicked in as intended to address oversupply, returning demand to auctions.

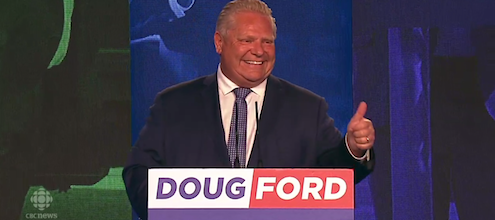

But despite these strengths, the incoming premier has been clear about his desire to dismantle Ontario’s cap-and-trade system. (He has said that he would “come down heavy on polluters” but it’s not yet clear what that means in practice.) Scrapping the system, however, will likely be a complicated, costly and drawn-out process. There are a few ways to go about it.

Complicated surgery

If the government is intent on leaving as quickly as possible, WCI rules require a year’s notice. On its own, this announcement could spark a sell-off. Ontario firms, now holding permits of uncertain value, would flood the market to mitigate their financial losses. This would depress the permit price, reduce certainty for businesses and investors, and could prompt legal action from the California Air Resources Board—whose litigiousness in the face of U.S. climate policy repeal is currently on display. It would be an unprecedented legal case with unclear outcomes, but clearly a potential liability to the Ontario taxpayer.

On the other hand, the government might try to avoid these outcomes by buying back the permits that Ontario’s large emitters have purchased. A recent legal analysis suggests this would cost anywhere from $2 billion to $4 billion dollars of taxpayer money, plus an additional $100 million in legal fees and settlements.

But there’s also another option. If Ontario’s incoming government is dead set on leaving the WCI, the easiest thing might be to wait. The current compliance period runs through 2020, and 158 of the province’s largest emitters have already purchased $2.8 billion worth of permits. Remaining in the WCI for this compliance period would give these firms opportunity to use the permits they’ve already paid for. But it would still leave questions about what becomes of the post-2020 permits that they hold.

Both the fast track and the slow track for leaving the WCI are messy and costly. Beyond the costs described above, these choices would also deprive the Ontario government of some $2 billion worth of revenues a year.

And in any case, leaving the WCI wouldn’t mean the end of carbon pricing in Ontario.

The federal backstop

If the provincial government eliminates cap-and-trade, the federal government would enforce its backstop under the Pan-Canadian Framework. Again, we have two paths here. Ontario could willingly opt into the backstop, as the PCs were planning to do under the People’s Guarantee. In this case, the federal government would implement a rising carbon tax on Ontario’s behalf and return the revenues to the province with no strings attached. (See here for more on what an Ontario transition from cap-and-trade to a carbon tax might look like).

If, however, the Ontario government resists the federal backstop, then they could lose control of what happens to the revenues. (It is highly unlikely the province will win its planned court battle with the federal government.) The federal government must return the revenues to the province, but not necessarily to the government. If the federal government were to rebate the money directly to households, Ontario’s system could look more like a carbon fee and dividend.

Willingly or unwillingly, the pan-Canadian Framework will come to Ontario if it leaves the WCI. If the PCs dig their heels in, they will likely lose control of what happens to the revenues. And regardless, by not being in a linked system, Ontario firms will end up with higher carbon prices than they have now.

Meeting halfway

Of course, the provincial government doesn’t have to do anything; they could stay in the WCI and let the system continue working as intended. But that doesn’t mean accepting the status quo. In particular, changing how revenues from the system are used represents a clear opportunity.

Ontario’s cap-and-trade revenues currently fund the province’s Climate Change Action Plan, a mix of programs to drive further emissions reductions in the province. Using the revenues in this way is required under Ontario’s Climate Change Mitigation and Low-Carbon Economy Act. But some gentle amendments to the Act could open up a world of options for Ontario’s cap-and-trade revenues, including financing the many promises the PCs made on the campaign trail. Plenty of other options exist for cap-and-trade revenues, including reducing the province’s budget deficit, cutting corporate or small business taxes, or expanding public transit.

Changing revenue use also presents an opportunity to do away with the Climate Change Action Plan’s inefficient subsidies, such as electric vehicle rebates, which our analysis suggests reduce emissions at very high cost.

Tread carefully

A new government means new challenges for carbon pricing in Ontario. And there are a number of paths the new government can take. Some offer a way to help fund campaign promises. Several others offer messy exits out of cap-and-trade with uncertain timelines and outcomes.

Ontario has a well-designed, functional carbon pricing system in place. Rather than start from scratch, the PCs could take the occasion to run with the good and recycle the revenues in a way that is consistent with their vision for the province.

Whatever the new government’s views on climate policy, their choice will have important implications for Ontario households and businesses. They should tread carefully.

1 comment

[…] around provincial and federal climate approaches. Later this year, the federal government will be imposing a carbon price on all Canadian jurisdictions that do not have carbon pricing programs in […]

Comments are closed.