Alberta’s coal phase-out as a benefit-expanding policy

Alberta’s Climate Leadership Plan is more than a carbon tax. It is a package of policies designed to reduce emissions. One of the cornerstones of this policy package is the phase-out of coal-fired electricity by 2030. But to what extent does this policy genuinely complement Alberta’s carbon price? Today, building on our previous blogs on gap-filling and signal-boosting policies, we explore Alberta’s coal phase out as an example of the third and final type of complementary climate policy: benefit-expanders.

What is a benefit-expander?

As our new report discusses, carbon pricing should be the foundation for driving significant, cost-effective emissions reductions. But other policies that complement carbon pricing can give us more bang for our climate policy buck. As our two previous blogs discussed, they might go after inexpensive mitigation opportunities that the carbon price cannot. Or they may strengthen the carbon price’s signal to make it work more effectively.

But climate policy isn’t always just climate policy. Some policies might offer more than GHG mitigation. Better cycling paths and public transit can reduce car use (and thereby GHGs) and improve urban mobility. Clean tech investments can reduce emissions as well as create employment and opportunities for export. In short, benefit-expanding policies can offer both GHG reduction and additional, non-GHG benefits. When we consider these co-benefits, a policy might not be as expensive as it seems at first blush.

But to be a genuine complement to carbon pricing, benefit-expanders need to achieve those benefits cost-effectively. Co-benefits can help improve cost-effectiveness, but their presence alone isn’t enough to justify a policy.

Old king coal

Under Alberta’s Climate Change Leadership Plan, the province will phase out coal-fired electricity generation by 2030. The regulation applies to six coal plants that would have otherwise been able to operate post-2030. In parallel, Alberta is introducing its Carbon Competitiveness Regulation (CCR) next year—its carbon tax for large emitters. The CCR will cover electricity generation, which means the two policies will overlap in their GHG coverage.

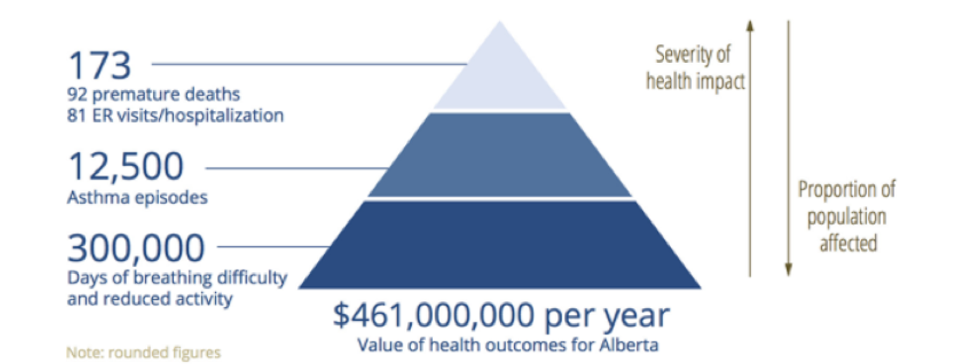

Alberta’s coal phase-out is a benefit-expander because phasing out coal generation will reduce the release of pollutants that impact public health. The health costs of coal can be significant: the Pembina study we reference in our report suggests that the health costs of Alberta’s coal-fired electricity are nearly $500 million per year, as seen in Figure 1. Phasing out coal would reduce these health costs—an important co-benefit that would lower the policy’s expected net costs.

Figure 1: Impacts on Albertans’ health from coal-fired electricity in 2015

Source: Pembina Institute

Many moving parts

To assess this policy’s performance in our report, we built a model of electricity supply costs and firm decision-making in Alberta. Our modeling suggests that without the phase-out, Alberta’s coal facilities likely would have been phased down in response to the CCR policy. This means that most of the GHG mitigation from eliminating coal would be attributable to the CCR. The coal phase out would only eliminate the reduced amount of coal generation that remained.

With respect to how much would have remained, it’s tough to say. The answer depends on how the electricity market in Alberta evolves between now and 2030—something made even more complicated by Alberta’s planned transition from an energy-only market to a capacity market.

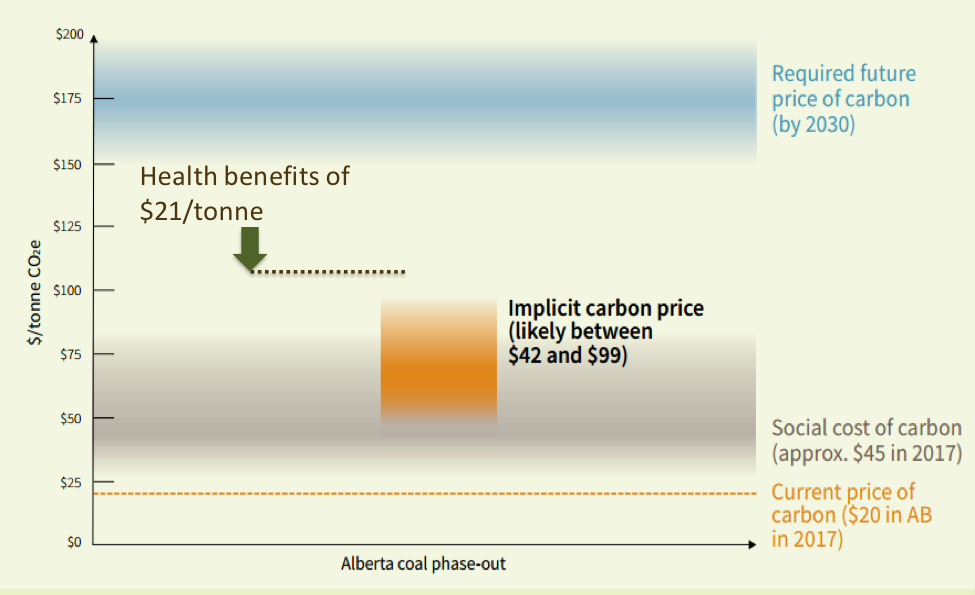

To account for this uncertainty in our report, we presented the policy’s estimated GHG reductions and costs in a range. Under the CCR alone, we might expect some coal facilities to hang around after 2030, operating at a capacity factor between 5 to 15%. This means that the policy’s cumulative GHG mitigation could be as high as 49 megatonnes, and as low as zero (more on that in a moment). This would lead to per-tonne costs between $42 and $99. Importantly, the health benefits of switching from coal to other electricity sources reduces the net cost of the policy—by about $21 per tonne.

As illustrated in Figure 2, these types of policy costs are benchmarked as mid-range: Their cost-per-tonne is above the current carbon price, but below where future carbon prices have to be for Canada to hit its 2030 targets.

Figure 2: Benchmarking the costs of Alberta’s coal phase-out policy

Because generation assets last for decades, one could argue that a policy with costs in this range could be justified as a forward-looking complementary policy (i.e., slow stock turnover in the electricity sector might mean that we want to think about policy costs relative to where carbon prices will be later, not where they are now). Overall, we say that based on available information, the policy might be complementary.

The latest

Since our report came out, we’ve heard some interesting comments and feedback. Sara Hastings-Simon and Binnu Jeyakumar at the Pembina Institute pointed out that the emissions intensity of coal plants rises at lower capacity factors. This could render the lower end of our capacity factor range (5-10%) uneconomical for coal-fired electricity producers, a change that would push estimated emissions reductions and costs towards the high and low end of their ranges, respectively.

Further, under Alberta’s new capacity market, coal plants might be more likely to hang on than they would have been under the energy-only market, waiting for competitors to go offline or for electricity prices to jump. This might also push our estimated GHG reductions higher and estimated costs lower.

The additionality question

These details have important implications for policy costs. More fundamentally, however, there are still questions around what the coal phase-out does that the CCR wouldn’t have. As we note in our report, the CCR might have driven out coal on its own (i.e., if by 2030 it was no longer economical to operate coal plants at any reduced capacity factor). In this case, the GHG mitigation attributable to the phase-out would be zero.

It’s obviously difficult to define this hypothetical case definitively. Some recent developments help shed a little light, but not a lot.

Coal plant owners affected by the regulation have recently signalled that they will close or repurpose their coal plants prior to the 2030 deadline. Some could argue that this announcement supports the idea that the phase-out was effective: plants that would have to close in 2030 are choosing to get on with it now. But critically, we don’t have the counterfactual case here. We don’t know whether the CCR or market forces alone would have led to this same outcome. This challenge exemplifies how hard it can be to disentangle the impacts of overlapping policies. And it points to the general importance of considering policy interactions when assessing climate policies.

Because of this additionality issue, some questions remain about the complementarity of Alberta’s coal phase-out policy. Overall, our findings suggest that the policy might be complementary to Alberta’s carbon price. It depends on how firms would have reacted to the CCR, and how the electricity market transforms over the next 13 years.

Not all co-benefits are measurable

One last note: There might be another, subtler co-benefit at play here. A full coal phase-out sends a message to other jurisdictions, both domestic and international, that Alberta is serious about reducing its GHG emissions. Beyond demonstrating that Alberta is not a laggard on climate, the coal phase-out might also embolden other jurisdictions in their own climate policy-making. Granted, this co-benefit is harder to quantify than health outcomes (which aren’t easy either).

Overall, the lesson from benefit-expanders is that any assessment of a climate policy’s merits should consider the full range of its potential co-benefits. Ignoring them can make a complementary policy seem more expensive than it is.

Comments are closed.