Unpacking the WCI: Hot Air Ain’t Cool

With our summer blog series on the Western Climate Initiative (WCI) winding down, it’s time to tackle one of its thornier criticisms: hot air. This is the claim that a chunk of the supposed emissions reductions from the cap-and-trade system aren’t genuine or real. If true, hot air could be undermining the integrity of the WCI system, with implications for Quebec, Ontario, and any other province or state looking to sign up. So is hot air a problem? And if so, how can regulators help get (or make) it right?

Is it hot in here, or is it just me?

California is a leader in implementing climate policies. But despite its efforts, the backbone of its climate policy —its cap-and-trade system —has been criticised of late. Critics, to varying degrees, point out some of the emissions reductions from its cap-and-trade system are not actually happening; that they are, in fact, hot air.

Two distinct problems lie at the heart of the issue: resource shuffling and carbon offsets. Both can compromise the quantity of actual emissions reductions in the WCI, but arise from two different aspects of the system.

Lost in the shuffle

Resource shuffling is when a firm under a cap-and-trade system preferentially switches higher-emitting resources for lower-emitting resources. In other words, it’s the intentional choice of firms’ (often electricity importers) to minimize the costs of regulation by swapping existing high-emitting contracts for lower-emitting contracts to reduce their carbon liabilities. So unlike classical leakage, where production actually moves to another jurisdiction, resource shuffling simply rearranges contracts from jurisdictions with stringent carbon policy to those with less stringent policy. This is why some call it an accounting trick that creates the false appearance of emission reductions.

The example of Southern California Edison (SCE) shows how humdrum the act of resource shuffling can be to an ordinary onlooker, and yet how big the impact can be on climate outcomes. Prior to the implementation of California’s cap-and-trade system, SCE imported electricity from a coal-fired facility in New Mexico. But once the regulation came into effect, SCE ditched its contract with the New Mexico facility, only for it to be subsequently bought by an Arizona utility. After all was said and done, emissions in California decreased from the transaction, yet production from the firm in New Mexico continued. The result? No real change in total global GHG emissions, getting dressed up as mitigation in California.

While the full extent of resource shuffling is unclear, the California Air Resources Board (the body that sets the regulations) reckons that the problem could be significant. On the lower end, an estimated 30 to 60 million tonnes of GHGs have leaked from the California market. But the leakage could be as high as 360 million tonnes if resource shuffling from other sectors, beyond electricity, is considered. Either way, both the low and high estimates represent a big chunk of the total emissions cap—compromising the effectiveness and integrity of the cap-and-trade system.

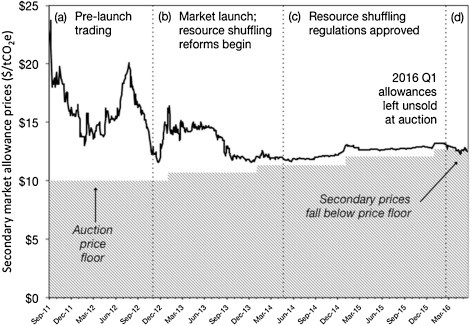

Aside from the direct result of driving fewer emissions reductions and undermining the cap-and-trade policy, evidence suggests that resource shuffling has also played a role in the recent drop in permit prices (discussed in a previous blog). By reducing firms’ carbon liabilities, resource shuffling lessens the overall demand in the permit market. The graph below shows that the price of permits on the secondary market actually fell below the price floor earlier this year. Again, the extent to which resource shuffling is responsible for low permit prices is unclear; however, this analysis shows how the crash in prices closely coincided with the loosing of rules for resource shuffling.

Resource shuffling was initially banned in the regulation’s original form, and even forced companies to attest they weren’t engaging in the practice. But a few months before the first compliance period, industry pushed back and lobbied against the ban. The official rules were eventually softened and created a range of exceptions that allowed the practice of shuffling to continue, largely unobstructed. Like clockwork, California utilities began divesting in long-term contracts with out-of-state coal-fired power plants.

The fact that California initially had a tight policy in place to prevent resource shuffling is reassuring that rules can be improved. So the logical place to start may be to enforce the tight rules that were already in place. Beyond this solution, another approach may be to make utilities financially responsible for resource shuffling, which could mean imposing penalties based on the size of the leakage. Alternatively, if regulators have good evidence that firms are swapping contracts to skirt their liabilities, the emissions cap could be reduced to reflect the leakage.

Neither of these solutions would be pretty: they require detailed information on the behaviour of individual firms and their emissions, which makes oversight a practical problem. But the good news is that more can clearly be done to stop resource shuffling from further undermining California’s cap-and-trade system. Moreover, as more jurisdictions implement carbon pricing, resource shuffling will become less of a problem.

The onset of concerns about offsets

The second concern of hot air in the WCI system is with carbon offsets. These are meant to provide added flexibility by offering firms the ability to purchase credits to meet their emissions reduction obligations. The money from purchasing carbon offsets directly finances projects that generate emissions reductions somewhere else, such as through renewable energy, forestry, or resource conservation projects. But, critically, in order to be counted as genuine emissions reductions, projects must meet a range of important criteria. In particular, projects must be scientifically verifiable and must pass the additionality test—i.e. that the projects would not have occurred without the offset funding.

(Just to be clear, here I’m talking about regulated carbon offsets in the WCI, not the voluntary variety.)

If done well, carbon offsets can make it less costly for firms to reduce their emissions, as some emissions reductions can be quite cheap. But critics raise some valid concerns about the integrity and credibility of carbon offset markets. If loosely regulated, carbon offset markets can be open to fraud (i.e. peddling questionable emissions reductions) which can undermine the credibility of the policy—just like resource shuffling. And if there’s an overreliance on offsets to meet compliance obligations, this can further weaken permit prices at government auctions.

Based on progress so far, it seems like concerns of offsets in California, and in the WCI more generally, could be overblown. First, firms in California (and also Quebec and Ontario) can only use offsets to meet no more than 8% of their compliance obligations. Moreover, evidence suggests that firms’ haven’t come close to reaching this limit. In the first compliance period (2013-14), for example, firms’ purchased only 15% of the allowable limit.

Second, regulators in California, Quebec, and Ontario have developed rigorous rules to ensure the offset credits are real, enforceable, permanent, quantifiable, additional, verifiable and unique. And while concerns about bunk offsets are reasonable, California has invalidated only a small number of offset credits so far.

Clearing the air

Concerns about hot air in the WCI should be taken seriously. Hot air—from either from resource shuffling or shady offsets—can chip away at the integrity of the cap-and-trade market and weaken permit prices. Ultimately, a balance must be struck between ensuring rules are tight enough to avoid leakage or dubious offsets, while also making sure that the rules aren’t so tight that they shut out viable mitigation opportunities. Finding the right balance will be an ongoing challenge as the WCI evolves, but will help deflate concerns about hot air.

Comments are closed.