Don’t Hate the Driver, Hate the Traffic

We take transportation policies personally, and we should. But when it comes to fighting congestion, instead of playing the blame game we need to change the game completely.

I have a confession to make: I drive a car.

Not all the time. But sometimes. Even though I live five minutes from a subway stop. Even though I own a bike (and, embarrassingly, an adult-sized scooter). Sometimes I choose to drive. For example, on Sundays, I drive to the grocery store because I’m shopping for a family of four (half of which seem to eat their body weights in goldfish crackers every week).

This morning, I drove to the gym. Yes, I could have biked. But I didn’t. Am I that person (gulp)? Maybe. But hey, I just wanted to get there and back early enough to see my kids off to school. And I’m not a very confident (or fast) biker, ok? So stop judging me.

Whoa. That got personal. Sorry. But actually, that’s kind of the point.

As it turns out, the decisions we make about how to get where we need to go are deeply personal decisions. They are shaped by where we live, where we work, when we work, what kind of job we have, our family make up, our income, our physical abilities and limitations. The list goes on. It’s because of this, I think, that discussions around new transportation policies and projects are often so heated and so polarizing.

Congestion pricing is a discussion worth having

In light of the news, earlier this week, that Toronto is considering further research of toll roads in the downtown, it wouldn’t be totally surprising for some of us to have an immediate, visceral, and personal reaction. But I hope we can take a step back. Because congestion pricing—whether in the form of toll roads, HOT lanes, city centre pricing or some other approach— is a discussion worth having, especially if we value our freedom to get around.

The problem is that while all of our lives are very different, too many of us are making the exact same choice: the choice to drive a car on the same road at the same time of day. That is the simple recipe for congestion. A problem that is plaguing Canadian cities, costing billions of dollars in lost time, exacerbating illnesses caused by air pollution and stress, and basically making our lives more miserable than they need to be.

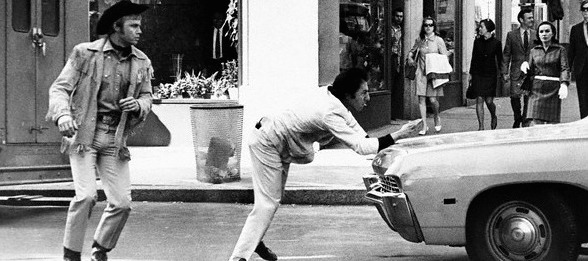

Just about everyone agrees congestion is a problem. However, when it comes to talking about the solutions, something weird happens. We end up fighting each other, instead of the traffic. And that fight almost always pins an imagined “driver” against an imagined “non-driver.” Who are these imaginary beings? And do they really live in and move about the same city that I do?

Okay, sure, there are some among us who always drive and some among us who never do—but the vast majority of us probably falls somewhere in the middle. Journalist Jeremy Klaszus described this phenomenon as a movement toward “creative commuting.”

“In 1999, 42 per cent of downtown [Calgary] commuters during rush hour were drivers, according to city data,” Klaszus writes. “By 2010 that had dropped to 35 per cent. The percentage of transit users, pedestrian commuters and cyclists all increased during this time.” Klaszus attributes this variety, sensibly, to a greater availability of choice.

Multimodal cities and incentives

We are seeing many cities embrace this idea as they engage in what is called “multimodal planning.” In a nutshell, a multimodal city offers and facilitates a broad network of transportation options and avenues—everything from bike paths, to carpool lots, to high-speed busses, to LRTs, to car shares. This approach recognizes that, as individuals, our transportation needs vary—by the season, by the week, heck, even within the same day.

The ability to diversify and customize our travel choices should help us cut down on congestion, right? After all, the more options I have to get from point A to B, the more likely I am to take advantage of those options. Well…yes, sort of, and not quite.

Clearly, more choices help and are necessary. But choices, on their own, don’t change incentives. What I mean is: if it’s still cheaper, faster and more convenient for me to drive my car by myself to work during rush hour than it is for me to take the subway or carpool or ride my embarrassing adult-sized scooter—guess which option I will likely choose. Guess which option most people will likely choose?

Congestion pricing is the key to making all of the different modes of transportation we’re investing in serve us better. Why? Because it adds something new and critical into our decision-making calculus. It sends what the Ecofiscal Commission calls a market signal. That signal helps me factor the cost of my “congestion contribution” into my choice to drive or to get there some other way or at some other time. That signal might even change based on where I’m going, when, and how many other people are going there too (this is what’s called dynamic pricing). This helps ensure that we don’t all end up in the same place at the same time.

Does congestion pricing mean that I will never drive my car again? No. It just means that I’ll make a more informed choice about where and when and how often to drive. And because it’s not just me—it’s everyone making more informed choices—that means when I do take to the road, there will be less people on it. Good.

As the City of Toronto and the province of Ontario both get serious about how congestion pricing could work around the GTHA, I hope we can give these ideas a fair shake. Let’s keep our imaginary frenemies—the always-only driver and the never-ever driver—at bay. And remember that congestion isn’t the fault of any single person or kind of person. Congestion is all of us. So, instead of hating the players, we need to change the game. That means not only more and different transportation choices, but smarter and better informed ones.

****

Jessie, our Communications Director, is the Ecofiscal Commission’s official wonk translator. Her blog series, Economics #4TheRestofUs, offers a layperson (um, human) perspective on ecofiscal issues and policies.

1 comment

So basically you are saying… we can`t do anything about traffic congestion. No matter how much R & D is spent, so let`s make a buck and support a model like 407 ETR that NEEDS traffic congestion to be viable. It doesn’t matter that we are using land put aside for public use. We can take it off the books, privatize and have those that can pay, have some relief and those who can`t… well too bad so sad peasants.

This is a fascists solution because the private enterprise needs the government in order for their business to be viable. Mussolini would have loved the idea. But capitalists will cry NOT FAIR!!!

I think I know what my next article will be on. By the way, you should stop by my blog Stop the 407 ETR`s Abuse of Power.

Comments are closed.