Can we improve the efficiency of carbon pricing and regulations?

The release of our final report yesterday highlighted Canada’s options for bridging the gap to its 2030 targets. Bottom line? There are only a finite number of approaches. We have regulations, subsidies, and carbon pricing. But the details of how governments design and implement those policies matters just as much as the choice of approach. This blog unpacks some of these details from our analysis.

More efficient carbon pricing is possible

Approach #1 in our report relies on carbon pricing to hit Canada’s 2030 GHG target. The core version of this scenario is inspired by policies we’ve already seen implemented in Canada. Yes, the stringency is much higher than current policies. But like the federal backstop, the policy returns revenue directly to households in the form of rebates. It also includes “output-based” carbon pricing for large emitters to address concerns around competitiveness. In fact, the scenario errs toward larger output-based support for industry, again paralleling the choices we’re seeing in output-based pricing systems across Canada.

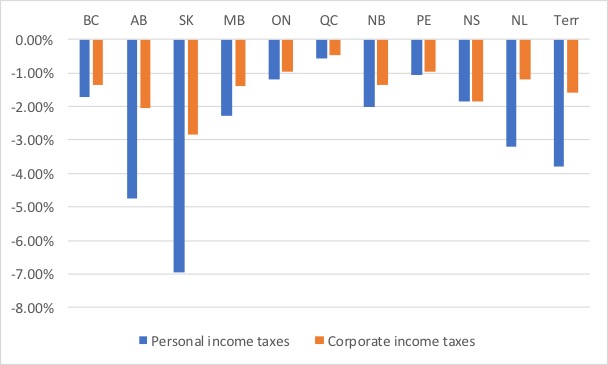

In theory, we can do better. In an alternative version of this policy package (found in Section 5 of our report), we limit rebates only to low-income households. The remainder of the revenue (85%) is used to reduce corporate and personal income taxes in each province (see the figure below to illustrate the magnitude of tax cuts possible). We also more narrowly target output-based support, freeing up additional revenue to invest in a tech fund. The result is a policy package that is even more cost-effective than our core carbon pricing scenario: Canadians’ average income is about $1,500 higher in 2030.

Figure 1: Projected income tax reductions (percentage points) in 2030 under more efficient carbon pricing

Is this improved package practical? Maybe. Providing rebates to all households rather than to some has seemed to be critical to support for the federal backstop carbon pricing policy. And industry has proven to be very capable of successfully lobbying for more, rather than less, output-based support. Still, the opportunity for lower cost carbon pricing is real.

More efficient regulations are also possible

Approach #2 considers our options if carbon pricing is off the table. The core version of this scenario includes a range of subsidies and regulations — again, inspired by existing policies across Canada — that collectively apply to emissions across the entire economy. Many of those regulations and subsidies are expensive themselves. And the package includes a range of overlapping or duplicative policies that force more emissions reductions in specific parts of the economy, raising overall costs.

An alternative, better-designed regulatory package makes several adjustments.

First, it eliminates subsidies, which tend to pick winners, can sometimes reward businesses and households for things they would have done anyway, and must be paid for using tax increases or greater public debt. All of these factors raise costs.

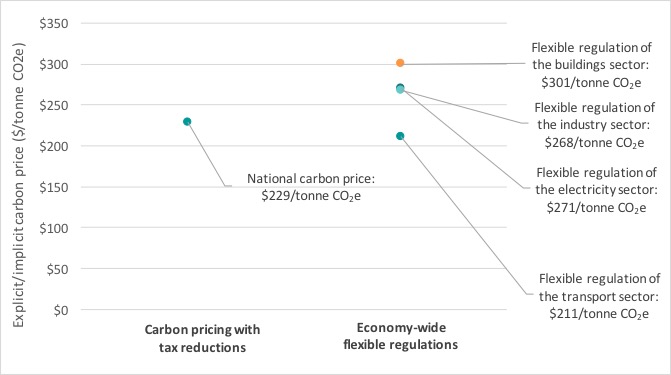

Second, it ensures all regulations are flexible regulations. Focusing on ends instead of means avoids picking winners. And allowing compliance trading lets regulated firms that have low-cost options for reducing GHG emissions do more, and firms that don’t to do less. Similar to carbon pricing, this approach leverages market forces to reduce costs.

Third, it ensures that the package of flexible regulations is coherent. Regulations do not overlap. And the stringency of each regulation is calibrated to the others as closely as possible, helping the package collectively drive lowest cost emissions reductions across the economy. The figure below illustrates the “implicit” carbon price across the set of regulations. It also contrasts it with the carbon price needed under an efficient carbon pricing approach.

Figure 2: Explicit and implicit carbon prices under efficient policy implementation

Under this more flexible regulatory package, Canadians’ average income in 2030 is $2,300 higher than it would be under the package based on existing regulations and subsidies. These gains are significant. The package of coordinated flexible regulation mimics many of the strengths of carbon pricing and performs nearly as well.

Is it practical? Again, maybe. Harmonizing the flexible regulations with each other was challenging in our modelling framework — where we had full control of the system — and would be even more so in reality, where an “implicit carbon price” only emerges after the fact. Furthermore, successful industry pressure to dilute the stringency of any one regulation would require increasing the stringency of another in the package in order to achieve the target. This would increase the overall cost of the package, highlighting the implementation challenges.

More efficient industry-only regulations have difficulty achieving Canada’s target

Approach #3 shelters households from direct costs. The core version of this scenario has regulations targeted only at industry and a range of subsidies that target things like home heating, electricity, and personal transportation. Hitting the target with this narrow regulatory approach requires very generous subsidies and high corresponding tax increases.

We can improve the economic efficiency of this approach by taking these high-cost subsidies out of the mix. But this means households’ emissions aren’t covered by regulations or subsidies—they’re exempted from climate policy altogether. To make up for this, the regulations focused on industry have to become very stringent. For example, industry as a whole has to by 2030 cut the GHG intensity of its production by a full two thirds relative to 2010 levels.

The problem is that industry can’t get there on its own (at least in our model). Even at high levels of stringency, flexible regulations on industry can’t deliver enough GHG reductions to get Canada to its 2030 GHG target.

The upshot is that we were unable to produce an economically efficient version of this approach that still achieves the target. Sheltering households from direct costs requires a heavy reliance on subsidies and corresponding tax increases that push us into recession. Or it means exempting households altogether and missing the target. So it’s a non-starter.

And then there were two

With the third approach off the table, how do the first two, more efficient, approaches stack up? The figure below shows Canadians’ average income to 2030 under each approach.

Figure 3: Projected 2030 GDP per capita under efficient policy implementation

Both approaches can deliver the emissions reductions required and maintain a strong economy. Reducing income taxes to improve economic growth is a worthy goal, especially for conservative-leaning governments. Alternatively, if governments are loathe to implement carbon pricing because of its visibility, a flexible, coordinated, economy-wide regulatory approach is a cost-effective alternative — if it can be implemented in practice.

Download the Report (PDF)

Comments are closed.