Ramping up: Ambitious climate policy returns to British Columbia

It’s been a pivotal few weeks for provincial climate policy. Ontario released its new climate strategy last week, scaling back provincial targets and replacing its cap-and-trade system with a mix of regulations, subsidies, and a pricing system for heavy emitters. Yesterday, the coalition government in British Columbia released its own newly-minted CleanBC strategy. Happy holidays, policy wonks!

B.C.’s new climate strategy is a package of ambitious measures that once again make the province one of the country’s climate leaders. Underpinned by the province’s steadily rising carbon tax, which will hit $50 per tonne by 2021, the strategy also adopts a range of other climate policies—beyond explicit carbon pricing—that will move the province closer to its 2030 emissions target. This blog takes a closer look at some of these policies and the extent to which they minimize the economic costs of climate action.

Digging deep

B.C. has been a leader on climate. In 2008, in response to the absence of meaningful national policy, B.C. implemented North America’s first economy-wide carbon tax. It started at $10 per tonne of GHG emissions in 2008, froze at $30 from 2012 until 2018, and will rise by $5 every year until it reaches $50, aligning it with the federal government’s carbon pricing backstop. We will have to wait and see what happens to the carbon price beyond 2021. B.C. has not ruled out further increases.

The carbon tax is working well and reducing emissions. But the current price trajectory of the tax will not be enough to reach the province’s ambitious climate target alone. And unlike several other provinces, B.C.’s electricity grid is already clean, which means the province has already plucked some of the lowest-hanging fruit for emissions reductions.

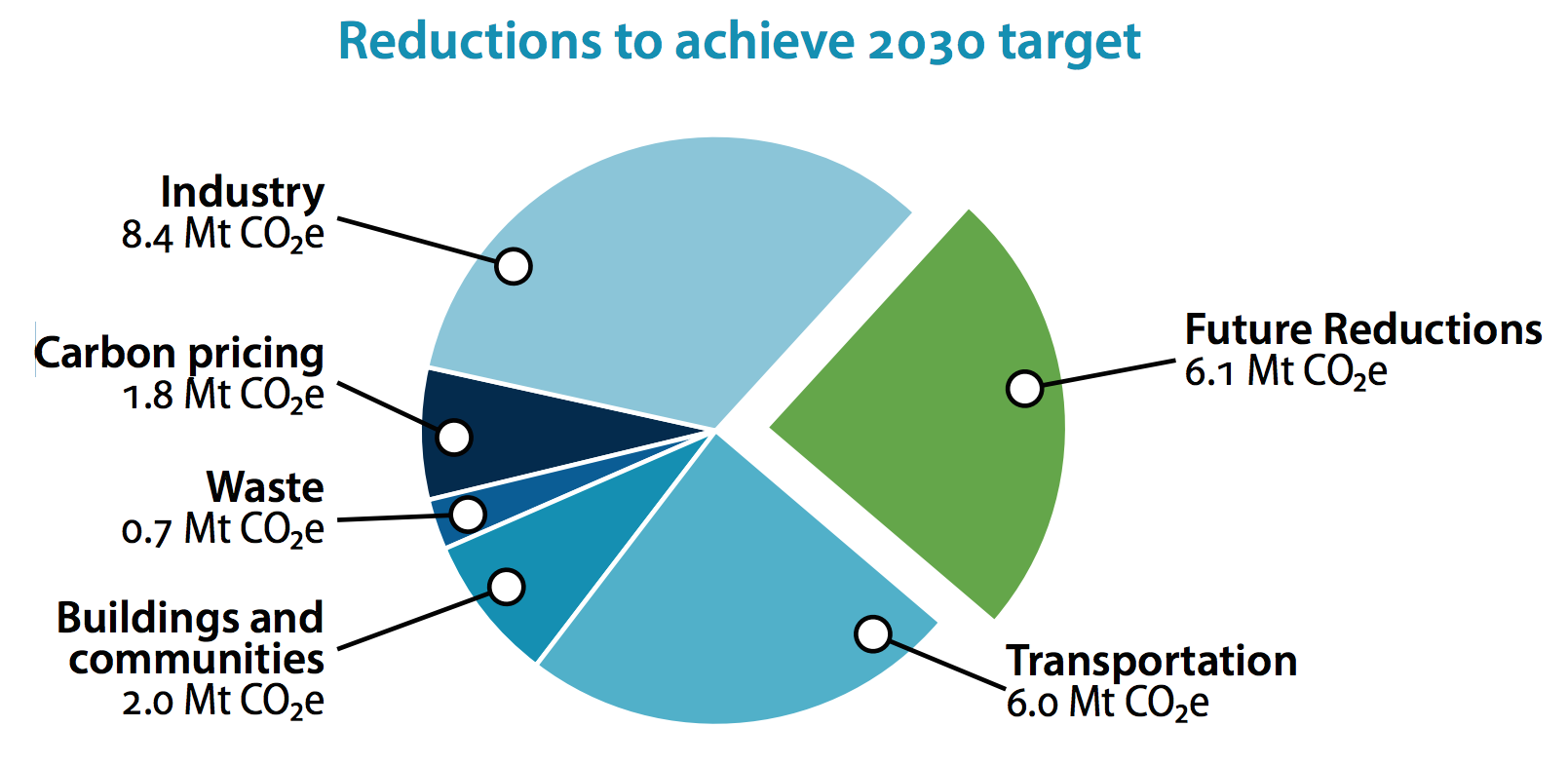

All told, B.C. needs to dig deep to reach its targets. The CleanBC strategy—fully realized—will get it 75% of the way (a plan for the remaining 25% will come in 2019). And instead of increasing the price of carbon emissions beyond $50 per tonne (which no Canadian government is seriously considering at the moment), B.C.’s strategy relies on other policies, in addition to the carbon tax, to do the heavy lifting (see figure).

But good climate policy considers costs alongside emissions reductions. And in terms of cost-effectiveness, not all climate policies are created equal. How do the different elements of B.C.’s strategy stack up?

Genuine complements to B.C.’s carbon tax

The B.C. strategy contains a few policies that will do things that carbon pricing can’t. These elements have a clear role to play as part of cost-effective package.

The strategy includes, for example, regulations that target methane leaks from the oil and gas sector. Since it’s difficult to measure and price these emissions, regulating them makes sense. And because methane that doesn’t leak can be sold (i.e. natural gas), these regulations offer a relatively cheap way to reduce emissions. The plan also includes other “gap-filling” policies, including waste diversion targets for organics and methane capture at landfills (although these policies may not work well together—diverting organics from landfills means there’s less gas to capture).

Some complementary policies in the plan have economic objectives. To protect competitiveness of businesses, energy-intensive and trade-exposed firms will be eligible for rebates on the amount of carbon tax they pay above the base of $30 per tonne of GHGs, based on their emissions intensity. The cleaner the technology, the bigger the rebate. Emitters using world-class technologies to reduce emissions will be eligible to receive a full rebate. The system will function very similarly to the output-based pricing approach in the federal backstop.

Embracing market principles

The biggest chunk of emissions reductions in B.C.’s plan (21%) come through flexible regulations for the transportation sector. The province implemented its low-carbon fuel standard (LCFS) in 2010, requiring fuel distributors to reduce the carbon-intensity of their fuels 10% below 2010 levels by 2020. The new plan ramps up the stringency of this policy, requiring a 20% reduction in carbon-intensity by 2030. Crucially, the policy is technology-neutral; it doesn’t care how distributors reduce their carbon-intensity.

B.C.’s strategy includes a second flexible regulation for zero-emissions vehicles (ZEV), which requires a certain portion of all cars sold in the province to be zero-emissions. It will be easier for some automakers to meet or exceed these quotas than others; automakers that can’t meet the quotas cost-effectively can buy permits from those that exceed the quota. This trading increases flexibility and helps bring down costs. Quebec adopted a similar regulation in 2018.

Taken together, these flexible and technologically-agnostic regulations will help drive significant emissions reductions at relatively low cost. However, it’s important to note that flexible regulations are still costlier than simply increasing the carbon price. The price of permits to comply with the LCFS, for example, is about $200 per tonne, well above the current $35 carbon tax.

Trimming the fat

Finally, some policies in B.C.’s strategy could come with an even higher price tag. Household rebates (e.g. home retrofits and some types of ZEVs), may be offered to people who were already going to take these actions. Even though these rebates make clean technologies more affordable for households, some emissions reductions will not be driven by the policy, which undermines its overall cost-effectiveness. Subsidies for ZEVs in Quebec, for example, cost about $395 per tonne of GHGs reduced.

There are also other policies that the province might be better off scrapping in favour of a higher carbon price. For example, B.C.’s new plan will require natural gas distributors to blend 15% of renewable natural gas into their supplies. If this were a cost-effective way to reduce emissions under the carbon tax, distributors would already be doing it. To induce this type of behavioural change, B.C. would be better off increasing its carbon tax beyond $50 per tonne.

Summary

Overall, the CleanBC strategy is meaningful and a step in the right direction. It should come as no surprise that our preference would be a carbon tax that goes above and beyond the $50 per tonne in 2021, allowing the government to rely less on policies that carry a higher economic cost. But if governments do choose to rely on regulations instead of higher carbon prices, they would be wise to follow B.C.’s lead in making those regulations as flexible and as market-driven as possible.

B.C.’s carbon tax has served as a model to the world and its new strategy builds on a history of leadership. And while there’s plenty more to come in 2019—including a full costing of the existing measures and detail on how the province will hit the remaining 25% of its target—this plan clearly shows that B.C. is again serious about climate action. The challenge for government will be to design these policies at the lowest possible cost for British Columbians.

Photo credit: Michael Ruffolo

9 comments

As EcoFiscal has highlighted in previous analysis, any discussion of any carbon pricing scheme must include both the price and the coverage, i.e. what percent of emissions are charged this price.

Did I miss the discussion of coverage in this assessment? In a article several years ago, EcoFiscal said the BC carbon price was only charged on 70% of the emissions, so the effective price is only $21 ($30 x .7). Is this still valid under the new plan?

Hi Tom,

It’s a great question. B.C.’s carbon tax covers 75% of the province’s emissions. The other 25% is uncovered for two main reasons. The first and biggest reason is that there are some emissions that are difficult to measure, and therefore hard to apply a carbon price to (methane from oil & gas operations, landfills, certain agriculture emissions, industrial processes, etc.). Roughly 20% of B.C.’s emissions fall under this category, and a lot of policies in B.C.’s new plan will fill in these gaps. The second reason is that governments sometimes provide exemptions. Farm fuel, for instance, is not subject to the carbon tax in B.C. If you’re interested in reading more about carbon pricing coverage, here’s a great paper by Dobson and Winter from earlier this year.

Did I miss the analysis of how the LNG plant will reduce its emissions and how BC will reach its targets when the plant comes on line?

Hi Susan,

You’re right in that any new LNG facilities in BC will increase its emissions and make it harder for the province to meet its climate target. The emissions forecast in the CleanBC plan assumes that the LNG Canada facility will be built in 2025 and so incorporates these additional emissions into its planning. The combination of policies in the plan – if fully implemented – would get the province 75% of the way to its target. Policies to reduce the remaining 25% of emissions is expected in early 2019. In any case, any new LNG facilities in the future (not factored into the CleanBC analysis) could mean that BC’s climate policies will need to be even more stringent.

It’s also worth noting that while more LNG development in BC will likely increase provincial emissions, the LNG could displace more emissions-intense fuels in other parts of the world. Estimating these emissions reductions is really tough (as it depends on assumptions about what fuels the LNG is displacing), but it’s possible that additional emissions in BC could be offset (in part) by displacing emissions elsewhere.

The lng plants would help the carbon footprint on a world scale reducing the amount of coal and oil burned at present in the world. less greenhouse gases will be emmited with this alternate fuel to power power generators. One has to look at the big scale of things. Not just Canada. We are into a large scale problem with global warming.

Did I see something about ocean pollution? I don’t think so. The disgusting mess Victoria makes in OUR ocean with raw sewage dumping should be headline news.

Hi Judy,

B.C.’s plan does talk about using sewage to turn methane into natural gas. As for raw sewage, there has been significant movement at all levels of government over the last several years. The federal government released new standards in 2012, and will require thousands of municipalities to upgrade their wastewater treatment systems or build new ones in the coming decades, Victoria included.

I’m confused, where does the money from the carbon tax go? Maybe a nice graff showing where this money is used would really help.

Hi Carolyn,

Thanks for the question. The answer is a little complicated, as different governments have changed how the carbon tax revenues are spent. The carbon tax was revenue-neutral (or even revenue-negative) for the first few years, where carbon tax revenues paid for cuts to corporate and personal income taxes, along with cheques for low-income and rural residents. Since then, revenues have been used to fund other government initiatives.

According to the BC government, new revenues from the carbon tax will go toward: 1) Providing carbon tax relief and protecting affordability, 2) Maintaining industry competitiveness, and 3) Encouraging new green initiatives. The exact details of how the revenues will be used are expected to be in BC’s 2019 budget. I hope this helps.

Comments are closed.