Up in the Air: A look at Ontario’s new climate policy

After coming to power, Ontario’s Progressive Conservative government got right to work on climate policy. Over the last six months, they’ve dismantled the province’s cap-and-trade program, loosened the province’s emissions targets, and taken the federal government to court over the carbon-pricing backstop; all the while, we were told a new plan was coming. Today, the PCs unveiled their replacement for cap-and-trade. This blog looks at what we know so far.

What’s the plan?

The biggest change in this plan is that Ontario will no longer rely on carbon pricing to reduce its GHG emissions. Gone is the broad-based price signal that makes cap-and-trade a powerful and cost-effective way of reducing emissions. Instead, the government will focus on regulations and subsidies—though there is a small pricing component.

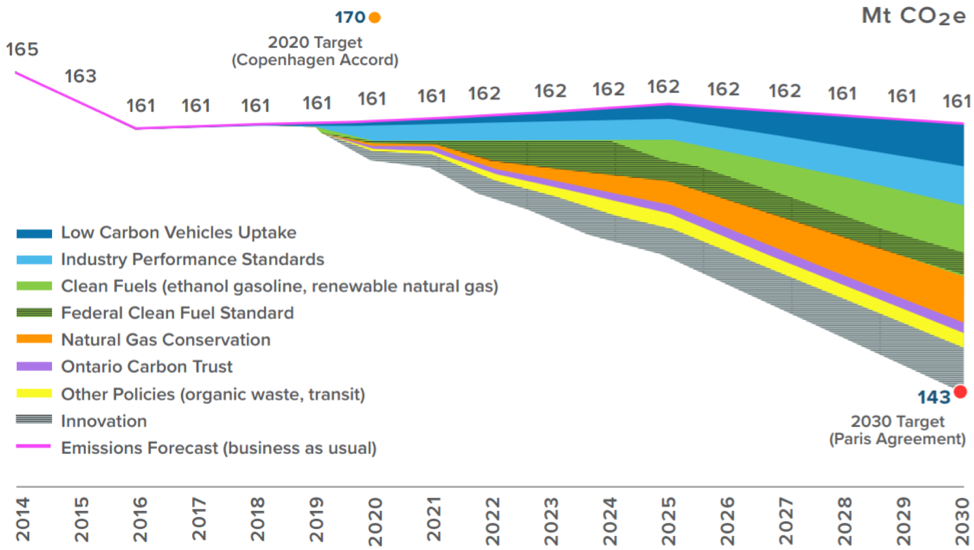

Below, we go over some key components of the plan, as summarized in Figure 1, as well as some important questions that are currently unanswered.

Figure 1: Ontario’s plan for reaching its new 2030 GHG target

Source: Preserving and Protecting our Environment for Future Generations: A Made-in-Ontario Environment Plan

Here are the key policies:

- Clean Fuels: This regulation will require fuel distributors to blend more ethanol in gasoline, moving from the current 5% to 15% by 2025. It also assumes that the mandate will not increase gasoline prices. However, analysis by Ecofiscal shows that ethanol mandates do increase pump prices and are a more expensive way to reduce emissions than a carbon price. If the price of blending ethanol is on par or cheaper than gasoline, why aren’t fuel distributors already doing it?

- Federal Clean Fuel Standard: The federal Clean Fuel Standard (CFS) is a broadly-scoped regulation that aims to reduce the GHG intensity of transportation and heating fuels in Canada. Interestingly, the Ontario government is counting on federal policy as one element in its plan. But two other regulations—Clean Fuels and Natural Gas Conservation are targeting the same fuels. Will these overlapping policies deliver GHG mitigation that is truly additional? To what extent will this overlap undermine effectiveness or increase costs?

- Industry Performance Standards: These performance standards closely mimic the federal government’s planned output-based pricing system—a form of carbon pricing. This is welcome news. But how will the policy achieve its intended emissions reduction target if it includes possible “across-the-board exemptions”, as the plan states? Were these exemptions factored into the analysis?

- Ontario Carbon Trust: This trust will provide $350 million in new funding for emissions reduction projects across the province. The Trust will both supplement private capital projects and fund emissions reductions projects through a reverse auction. But what will the criteria be for project selection? Who will administer the fund? And who will provide oversight and accountability? (Australia has a similar program; we get into the details below.)

- Innovation: This item includes potential advancements in energy storage and cost-effective fuel switching from carbon-intensive fuels in buildings to electricity and lower carbon fuels. But how—specifically—will these reductions be realized? What assumptions went into estimating the GHG reductions they will drive?

Questions about implementation are just as challenging. All of these policies will be difficult to implement in a cost-effective and coordinated way.

The Ontario Carbon Trust’s sister, down under

To illustrate some of those challenges, let’s take a closer look at just one of the elements of Ontario’s plan: the Ontario Carbon Trust.

Ontario’s new Carbon Trust is not without precedent. Australia has a comparable (though larger) system, implemented in similar circumstances. After repealing its national carbon tax in 2014, Australia brought in an Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF). Under the ERF, organizations apply for cash to fund emissions reduction projects.

So, how has Australia’s system worked? Not especially well. The program has proven administratively burdensome, money is running out quickly, and many projects that have received funding are not delivering the emissions reductions they promised. On top of this, there’s no way to know whether the ERF is paying businesses to take on projects they would have done anyway. As a result, the government has already started loosening its emissions caps, which aren’t even five years old.

Ontario can learn from and improve on Australia’s experience, but the fundamental issues with this type of instrument remain: it requires new revenue sources; it requires additional layers of administration; it will likely fund some emissions reductions that would have happened anyway; and it doesn’t offer economy-wide incentives to reduce emissions.

Costly and/or ineffective

Zooming out from the Carbon Trust, what can we say about this plan as a whole?

First, make no mistake, this new plan will have costs for Ontarians—like any meaningful climate plan. Industry will pass the costs of performance standard compliance on to its consumers as much as it can; the regulations will have compliance costs for Ontario’s households and businesses and administration costs for government; and funding for the subsidies will have to come from somewhere, either through increasing taxes, increasing debt, or cutting funding elsewhere.

Second, because the new plan focuses on a narrower set of activities and sectors, its total costs will be higher than under a broad-based carbon price. And unlike a policy package featuring carbon pricing, Ontario’s plan will not generate a revenue stream that can offset those costs for households. (The PCs could instead have kept cap-and-trade and simply made it more conservative, scrapping subsidies and offering a broad-based tax cut instead. But here we are.)

Third, it’s not clear that the plan will even get Ontario to its new, less ambitious target. There’s no transparency on how the emission reduction numbers were developed. The plan provides little detail on what the proposed policies will look like, how they might interact with each other, or what kind of technological and behavioural change they assume. As it stands, it is not clear that Ontario can reach its new 2030 target with this plan.

The bottom line is this: Under its new climate plan, Ontario will either hit its target at a higher cost, or it will miss it.

6 comments

AB is up next – election next year with Jason ‘no carbon tax’ Kenny leading in the polls, and no one selling broad based carbon pricing very hard here. I’m horrified at the prospect – AB has a long way to decarbonize, we need the cheapest way -and I know that’s broad based carbon pricing. Thank you for helping expose the pitfalls of the regulation/subsidies approach.

Hopefully, when Ontario comes out with their final strategy they will move to abandon ethanol which real science has shown doesn’t actually reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

There are algae-derived biofuels that aren’t as acidic, don’t destroy engines and actually help the environment!

This article shows a plan for conservatives to send money to conservatives without actually doing anything for the province they were elected to represent.

Approximately 15% of Ontario’s electricity generation capacity, which is carbon free, is available for sale as intermittent electricity for fossil fuel displacement. The potential cost savings for people in rural Ontario who do not have access to pipeline natural gas, is in the range $1 billion / year to $3 billion / year. Unless and until the current Ford government pursues this matter I will be unimpressed. Through this single measure alone they could meet their CO2 emission reduction undertaking.

Our local ratepayers association reduced emissions locally by targeting two cabinet makers that were emitting over 600 tonnes of emissions from spraying and painting into the local air. One of them refused to invest in environmental measures and was done in by the 2007 financial crisis. The other installed a Regenerative Thermal Oxidizer reducing their emissions to almost 0. Getting the MOE of Ontario to actually do their job, i.e. properly measure the emissions and enforce improved Certificates of Approval was the hardest job.

We do not believe in carbon taxes. We think globally and act locally. We forced the MOE to apply proper regulation and enforce it eventually. Carbon pricing is a lazy way for politicians to appear doing something yet all they do it impose more taxes on the public.

We do not mind paying more as long as long as we achieve clean air locally. If other citizens behind their computers did the decades of legwork we have done instead, this would be a wonderfully clean world.

Hi Alena,

Thanks for the comment. Acting locally is a key piece of the puzzle, and your example speaks to the importance of monitoring and enforcement.

The problem is that your example isn’t scalable or transferable. There are plenty of other emissions sources that that regulation would not work for, and it doesn’t offer any broad, economy-wide incentive to reduce emissions. Carbon pricing can provide that incentive, and it cares about degrees. Reducing emissions by 2 tonnes is better than reducing emissions by 1 tonne. It’s not an all-or-nothing proposition. Carbon pricing acknowledges that there is a cost to reducing emissions, and doesn’t force anyone to take any specific actions. And if the revenues are returned to citizens and businesses (which the federal carbon tax will do), then it doesn’t have to cost us more overall.

The other key advantage, as you alluded to in your example, is that a carbon tax requires very little enforcement. Governments implement the tax much like they would any fuel tax, and then let the market go to work. If you’re avoid the carbon tax, you’re reducing your emissions.

Comments are closed.