Carbon pricing works in Japan

Cities stand on the front lines of climate change. They’re responsible for over 70% of global emissions and they’ll bear the brunt of damages that result. They’re also laboratories for climate policy, from ultra-low emissions zones to net-zero buildings to literal urban jungles, and now, carbon pricing. As part of our long-standing series on international carbon pricing systems, we’re taking a look at the Tokyo ETS, which has operated quietly for a decade.

First of its kind

Tokyo’s emissions trading system (ETS) was ground-breaking in numerous ways. It was the world’s first municipal emissions trading system. It also applies exclusively to buildings, about 1,300 commercial, residential, and government facilities that account for 0.2% of the building stock and 20% of Tokyo’s emissions overall. In 2016, Tokyo emitted 66 megatonnes of GHGs, roughly British Columbia’s entire GHG footprint.

The Tokyo ETS doesn’t exactly function like a typical ETS. In practice, it operates more as a baseline and credit system. Facilities chose their own emissions baselines, the average of their best three years from 2002 to 2007. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG) then assigns free allocations to each building for each compliance period. The cap is the sum of all allowances. Operators have access to five types of offset credits. They ranged from US$60 per tonne to US$160 per tonne during the first compliance period.

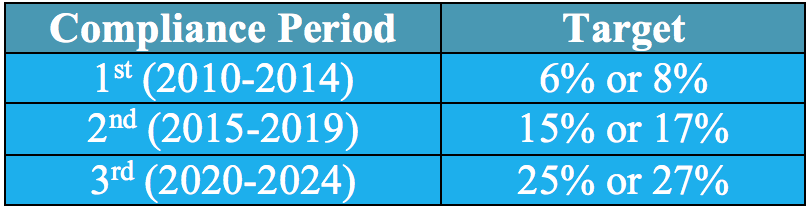

The TMG differentiated targets across buildings depending on the nature of their operations—for example, how much district heating they use. Additionally, new buildings that meet the criteria must enter the program. Existing buildings can drop out if they fall permanently below inclusion thresholds.

Early returns

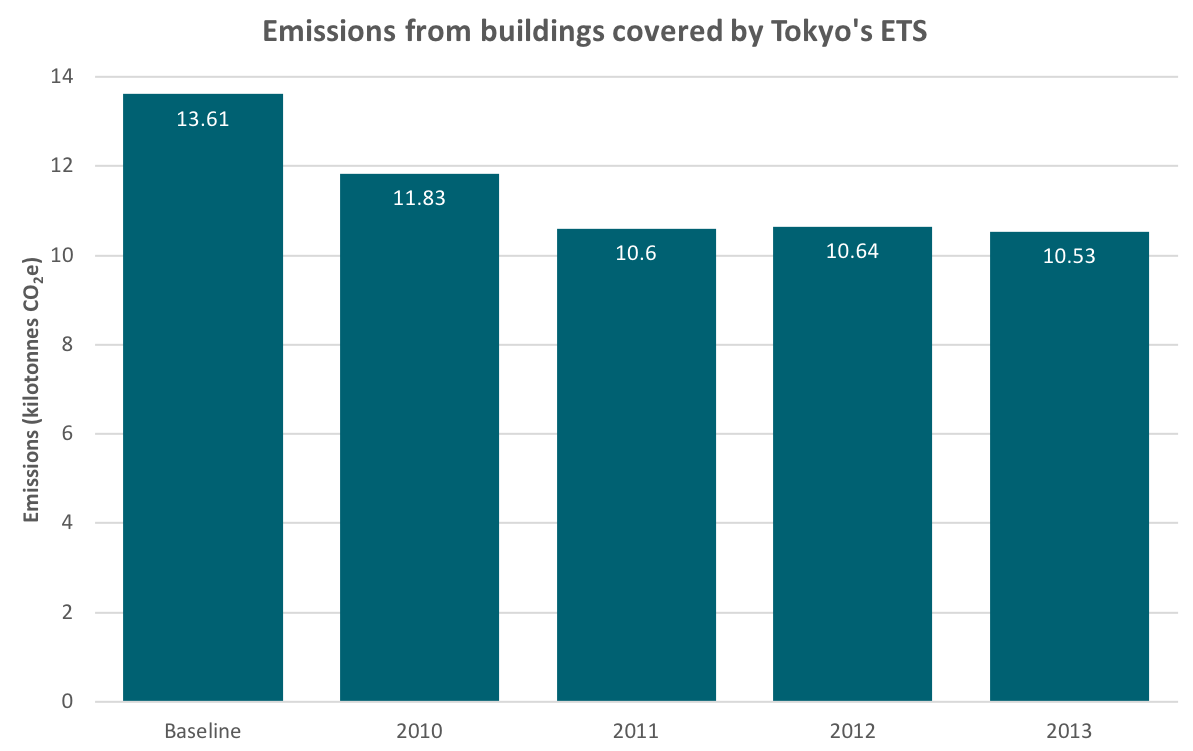

Participants met targets way ahead of schedule. By 2013, the average building reduced emissions by 23% relative to baselines, and over 70% of buildings had already hit their targets for the second compliance period, which ends this year.

Source: TMG, 2015

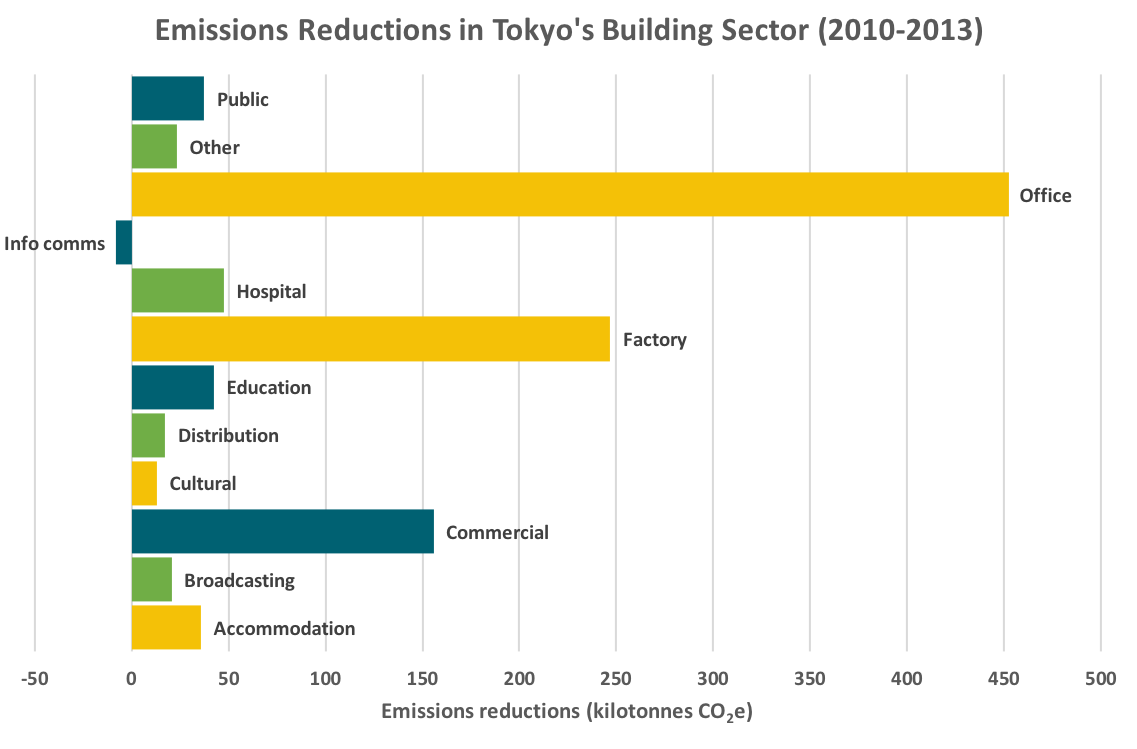

Over 78% of reductions came from offices, factories, and commercial facilities. Installation of high-efficiency heating and lighting retrofits were two of the most common initiatives.

Source: Roppongi et al., 2016

In 2017, covered facilities had reduced emissions by 27% on average, which is the facility-level target for the third compliance period ending in 2024.

Secrets of success

Let’s walk through a few of the factors responsible for the early success of Tokyo’s ETS.

Planning ahead

The ETS launch was preceded by many years of planning and data collection. In 2002, the TMG required its largest buildings to develop five-year emissions reduction plans and encouraged building operators to undertake voluntary emissions reduction initiatives. This early capacity building allowed operators to successfully navigate the ETS when it launched. In 2008, TMG expanded these initiatives to over 30,000 facilities.

Early planning gave building operators ample time to better understand their energy profiles. Careful, deliberate engagement with a broad set of stakeholders over several years helped bring everyone along as willing partners.

Containing costs

For buildings that couldn’t hit their targets as quickly, several design features helped reduce costs (though some potentially at the expense of optimal environmental outcomes). The TMG assigns a large majority of permits for free based on historical performance, permits banking, and awarded partial credit for early action.

In addition, operators have access to five types of offset credits: renewable energy credits, excess emission reductions credits, and Saitama credits (Tokyo’s ETS is linked to the Saitama prefecture). There are also small and midsize facility credits, and outside Tokyo credits. For these two credit types, the 30,000-some facilities that are not covered by the ETS can apply for credits if they can demonstrate additional emissions reductions. They can then sell these credits on the market.

This surplus of compliance options has limited trading between entities. Operators seem to prefer dealing with TMG rather than each other. More cap, less trade, but plenty of options for operators.

Name and shame

On top of strong monitoring and enforcement, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government singles out and honours buildings and companies that install best-in-class technologies or practices.

On the flipside, buildings that fail to meet their targets are shamed publicly, and then required to reduce emissions beyond their original target plus 30%. Shaming ultimately proved unnecessary. Compliance was 100% after the first phase.

Shaped by tragedy

It is hard to understate the impact of the Fukushima Daichii disaster on Japanese attitudes toward energy. Nuclear is now a non-starter, and the country has had to bolster its fossil fuel use in response.

The design of Tokyo’s ETS neatly overcomes this challenge. By targeting end users rather than suppliers, it prioritizes energy efficiency over fuel switching. Tokyo’s ETS can continue to perform despite the strong public aversion to Japan’s most widespread zero-carbon power source.

However, these countervailing forces can’t continue indefinitely. How long can efficiency measures offset emissions from a grid that’s getting dirtier? Absent stronger federal policies, the ETS may just end up pushing emissions upstream. Municipal action cannot replace national action, but it can definitely supplement it.

A new template

The Tokyo ETS was the first of its kind. It’s not your traditional price on carbon, but it still works.

Cities are increasingly taking their fate into their own hands on climate, and buildings are a key piece. Last year, 19 major cities pledged to make all new buildings carbon neutral by 2030. More recently, New York City announced a massive plan to slash existing building emissions 40% from 2005 levels in 10 years. Tokyo’s experiences—monitoring and enforcement, stakeholder engagement, policy mechanics—will be instructive.

Well-designed carbon pricing can take many forms and work anywhere, at any scale. The Tokyo ETS is one more data point.

Comments are closed.