How are governments recycling carbon pricing revenues?

If they don’t already, every province in Canada will soon have a price on carbon. The main purpose of carbon pricing is to reduce emissions, but they also generate revenues for governments. When it comes to recycling these revenues back into the economy, governments have plenty of options. In this blog, I’ll dive into the data and take a closer look at the approaches different governments are taking, including the federal backstop that took effect this week in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and New Brunswick.

A buffet of choices

Several provinces have already put their own carbon pricing systems to work, recycling the revenues as they see fit.

As of April 1, the federal government has designed a “backstop” carbon pricing system for provinces that don’t have one of their own. A key feature of the backstop is that it will return all carbon-pricing revenues to the province where they were collected. But for provinces that haven’t willingly adopted the backstop, the federal government chooses how they are spent, not the province.

The federal backstop will fully or partially operate in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Yukon, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, New Brunswick, and P.E.I. The remaining provinces have or are designing their own systems. As the figure below shows, they have established very different priorities for the revenues.

Sources: Government of Quebec, 2013; Government of British Columbia, 2018; Government of Alberta, 2019; Finance Canada, 2019

There’s a lot going on here. Let’s unpack a few key ideas.

First, provincial governments are using carbon pricing revenues to address multiple priorities. B.C. emphasizes affordability and competitiveness, while Alberta is focusing on diversifying their economy. Quebec’s main priorities are public infrastructure and further decarbonization. These three approaches contrast with the federal government, which is prioritizing simplicity and affordability by rebating an average of 89% of the revenues straight to households in backstop provinces. The remaining 11% will support small- and medium-sized enterprises, and municipalities, universities, schools, and hospitals (SMEs and MUSH, respectively).

Second, there are no right answers. Our research shows that a mix of corporate and personal income tax cuts are best for economic growth. But some governments are opting for other priorities—addressing market failures, enhancing economic equality, or investing in physical or social infrastructure.

Finally, note that the bars illustrate relative sizes of revenue recycling priorities, not total revenues. The total revenue generated in a given jurisdiction is determined by overall emissions and specific policy design choices, such as the price per tonne, coverage, and foregone revenue (given output-based allocations).

Oddities of revenue neutrality

There’s an odd wrinkle with B.C., which has the oldest economy-wide carbon tax in Canada. The carbon tax itself has survived multiple governments and mandates, but the approach to revenue recycling hasn’t. In last year’s budget, B.C. repealed the requirement for revenue neutrality, leaving the door open to recycle new carbon revenues towards other objectives, including additional mitigation and affordability.

We can’t know whether B.C. would still have pursued these initiatives if its carbon tax was higher or lower than $40/tonne, or if it didn’t have a carbon tax at all. Governments that don’t have a carbon price still invest in projects that reduce emissions (e.g. public transit). Would B.C. still invest in specific initiatives without a rising carbon price? If so, how much? These are, unfortunately, questions without clear answers.

Works in progress

What about the other provinces? Well, they’re not as far along. Nova Scotia plans to recycle its cap-and-trade revenues into a Green Fund to support “a broad range of measures that help reduce GHG emissions, mitigate social and economic impacts, or adapt to the impacts of climate change.” We’re awaiting details, but this sounds quite similar to Quebec’s approach. Thanks to free allocations, the revenue generated in Nova Scotia should be quite modest—especially in the medium term.

Newfoundland & Labrador are going with a carbon tax, but haven’t yet outlined a revenue recycling program. Ditto for P.E.I., which is adopting the federally-designed industrial pricing system but designing its own levy for small emitters and non-EITE sectors. PEI has made clear that all carbon-pricing revenues from gas and diesel will go “directly back to Islanders.”

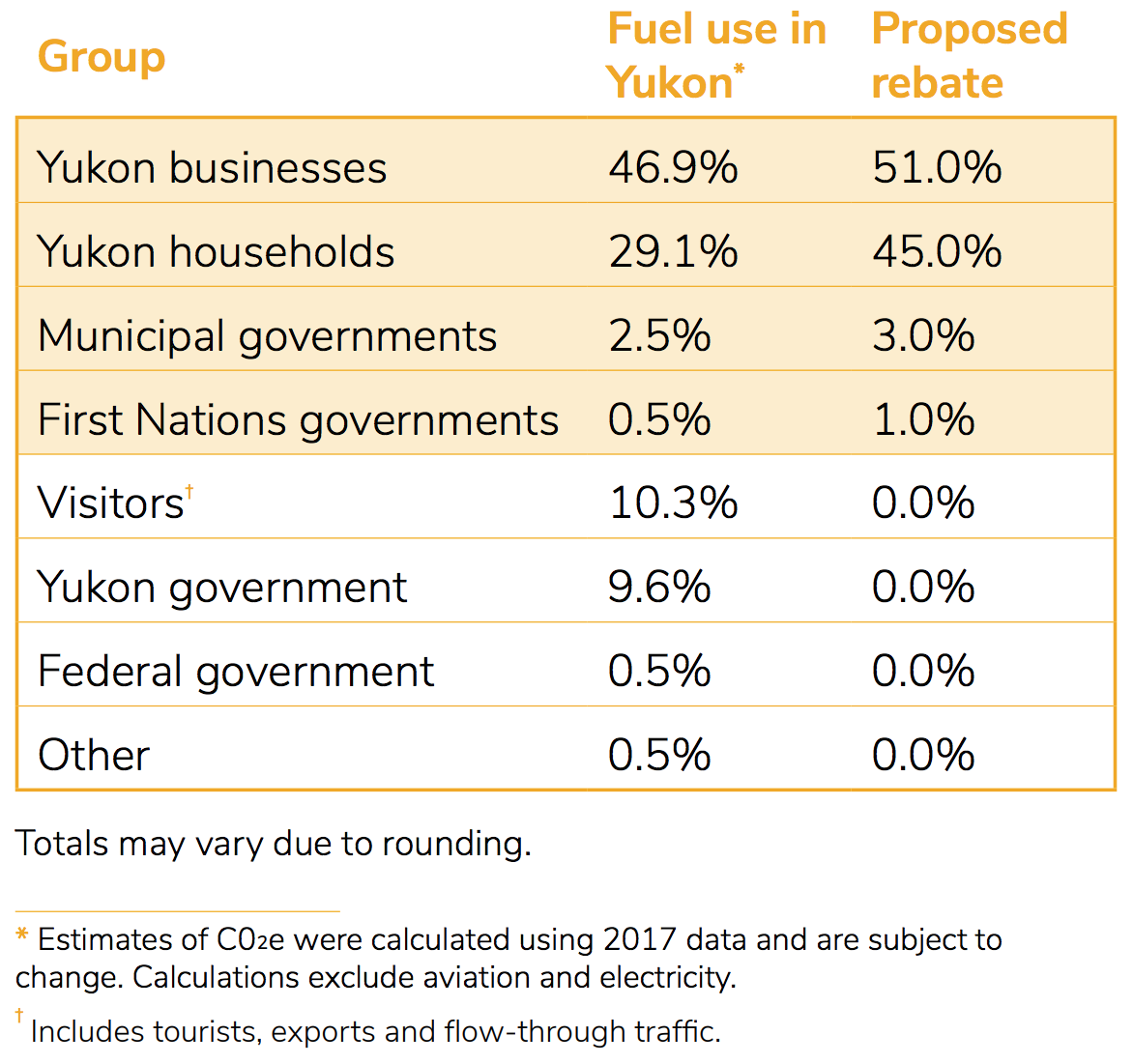

Yukon and Nunavut are in a unique position. Both territories requested the federal government implement the backstop for them and will retain control over the revenues as a result. Nunavut hasn’t made anything official, though they used a pure fee-and-dividend model in their impact analysis. Yukon will rebate the revenues to households, businesses, municipalities and First Nations.

Source: Government of Yukon, 2019

Decisions, decisions

It’s important to remember that Canadian governments aren’t setting the revenues from carbon pricing on fire; they’re earmarking them. They are addressing public priorities and helping Canadian households and businesses adjust and prepare for the low-carbon economy.

Revenue recycling is all about trade-offs, and different approaches will drive different economic and environmental benefits. Canadian governments have choices. They should make sure they choose wisely.

Comments are closed.