On Provincial Climate Policy and Early Action

When it comes to provincial climate policy, not every province is starting from the same place. Some, for example, have previously implemented policies to reduce GHG emissions. Should provinces be able to use these “early actions” to justify implementing less stringent carbon pricing policies now? In short, no. Here’s a slightly wonkish explainer.

How to think about stringency

First, a little context.

Canadian provinces have put forward plans for carbon pricing. As defined under the Pan-Canadian Framework, those carbon pricing policies must have a minimum level of stringency: provinces can choose carbon taxes that rise to $50 / tonne by 2022, or cap-and-trade systems with declining caps that require equivalent emissions reductions. BC’s carbon tax, Quebec’s cap-and-trade system, and Alberta’s hybrid approach all expected to meet the requirement for minimum stringency.

That consistency in stringency helps to minimize overall costs. Under a broad carbon price, businesses and individuals have incentives to take any actions that reduce GHG emissions that cost less than the carbon price. They’d rather avoid paying the price, if it makes economic sense to do so.

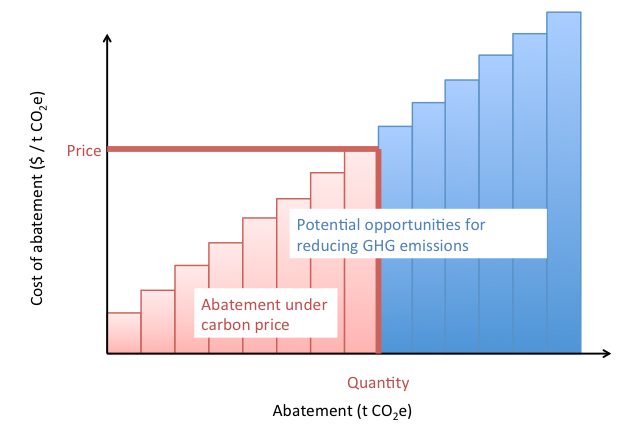

Let’s formalize that idea slightly. Figure 1, below, shows a “marginal abatement cost curve.” We can think of it as all the actions that are available to reduce GHG emissions—shifting to a more efficient furnace, replacing coal-fired electricity with natural gas or renewables, etc.—ranked in order of costs. The width of each bar represents the amount of emissions reductions that result from the action and the height is the incremental cost of achieving those actions. As the figure shows, carbon pricing would drive the actions that cost less than the price of carbon (i.e. the ones in red).

Figure 1: marginal abatement cost curve and carbon price

There’s one more important piece here: we can add up the area of all the red bars to obtain the total cost of this abatement. A broad carbon price minimizes the overall cost of achieving a given level of emissions reductions by letting market forces drive the lowest-cost abatement.

How to think about early action

But what if a province has already made some decisions about where and how it wants to reduce its emissions? Maybe it has invested in clean electricity infrastructure. Maybe it has already put in policies to encourage energy efficiency in buildings or changes in its vehicle fleet. In these cases, governments have implemented policies to drive specific “early actions” to reduce GHG emissions.

Now, what if a province that’s already taken early action also implements a carbon price? There are two cases that matter here.

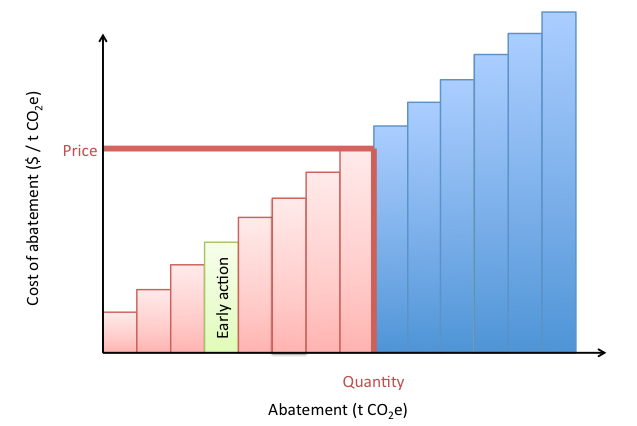

First, let’s consider case 1, in which “early action” previously taken to reduce GHG emissions was relatively inexpensive. Figure 2 illustrates. Once again, the carbon price only drives actions that cost less than the price of carbon (red). But previous policy means that one such action (i.e., the green bar) is not available: essentially, that bar no longer exists. As a result, abatement under the carbon price is less expensive overall: emitters have already taken action to reduce those emissions and already paid the corresponding cost. The carbon price doesn’t require additional action to make up the difference.

In effect, the carbon price automatically accounts for the previous action. Taking early action offers its own reward.

Figure 2: Early action and carbon pricing abatement, Case 1

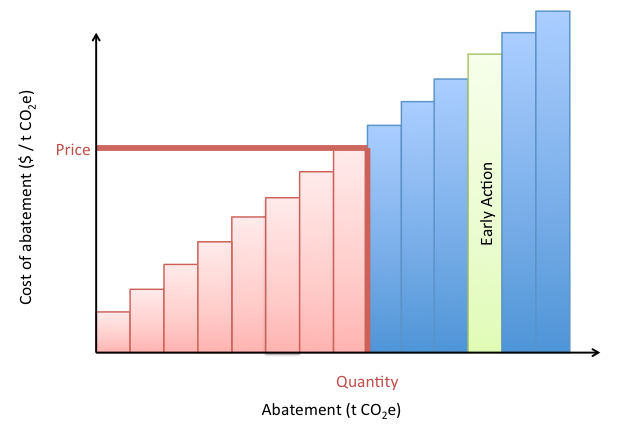

The second case, as illustrated in Figure 3, below, is a little more complex. In case 2, the early action to reduce emissions was more expensive per tonne than the price of carbon. There are two implications:

- First, all emissions reductions from the carbon price (red) are additional to previous action (green). In other words, the early action doesn’t lower the total cost of the abatement — that is, the costs of actions emitters take to reduce emissions — under the carbon price.

- The early action does, however, lower the costs of the carbon tax to the emitter. Had that early action not previously been taken, the emitter would pay the carbon price for the corresponding emissions. Having taken that action—effectively removing the bar from the MAC curve—it avoids paying the carbon price.

Figure 3: Early action and carbon pricing abatement, Case 2

How to think about early action in terms of achieving our national targets

In either case, early action doesn’t change the logic of moving toward a common, consistent carbon price across the country. Trying to account for early action by allowing a province to implement less-stringent carbon pricing, for example, would mean forgoing relatively inexpensive emissions reductions. That means diluting the incremental emissions reductions from carbon pricing, making it harder to achieve the national targets we have set out for ourselves. Or it means making up the difference with higher cost emissions reductions elsewhere in the economy.

There are also practical problems: how far back should we go, and what actions should we include? Should we account, for example, for decisions to build hydroelectric dams or efficient buildings or electricity transmission lines, even if climate objectives were secondary or even tertiary concerns at the time? To what counterfactual should we compare current emissions to assess the significance of previous actions? Would these actions have happened even in the absence of policy? In most cases even quantifying emissions reductions from past action is impractical.

How to move forward, practically and efficiently

Early action are in the past, as are the costs and benefits associated with them. Both those costs and benefits are now sunk. Our challenge now is how we move forward. Carbon pricing can target the lowest-cost emissions reductions available going forward, irrespective of previous action. Given the scale of the challenge required to meet our targets, a focus on driving additional, cost-effective emissions reductions should be the top priority.

Comments are closed.