The glass is half-full, but nobody wants to pay for it

In the spirit of water week, the Royal Bank of Canada released its annual water survey as part of its Blue Water Project. The survey makes clear that Canadians value clean water, and want policies that encourage sustainable water management. Surprisingly, however, the survey also finds that an overwhelming majority of Canadians are reluctant to pay for drinking water and sewage services. Canadians see the glass of water half-full, but nobody wants to pay for it.

Through the looking glass

The RBC survey shines some much-needed light on Canadian attitudes towards water, and illustrates a complicated relationship. The majority of Canadians see water as an essential part of the Canadian economy. Almost all Canadians surveyed believe water is a human right, and more than half of Canadians strongly believe water is a core part of our Canadian identity.

The survey also shows that Canadians see government policy as an important factor in protecting and managing water resources. Drinking water was listed as one of the highest priorities for government funding, second only to health care (sewage collection/treatment was fourth on the list). Nearly half of respondents think governments should tighten the rules for water use by industries and municipalities.

But just as Canadians put a high value on clean water and expect top-notch levels of service, the survey shows that few people want to pay for the full cost of protecting, treating, and delivering water. Only 20% of respondents strongly agree that households should pay the full cost of water services (another 46% somewhat agree). A mere 9% think that households should pay more.

No such thing as a free lunch… not even for water

There is a clear gap between how people value water and the price they are willing to pay for it—even though the RBC survey indicates that Canadians recognize that water infrastructure costs a lot of money and government resources.

This discrepancy seems to suggest that Canadians want their water supply infrastructure to be subsidized by government. And in fact, that’s exactly how Canadian municipalities have historically managed drinking water and sewage services. They have charged less for access to clean water than the infrastructure actually costs. Only recently have some municipalities begun to charge water rates that approach the full cost of service.

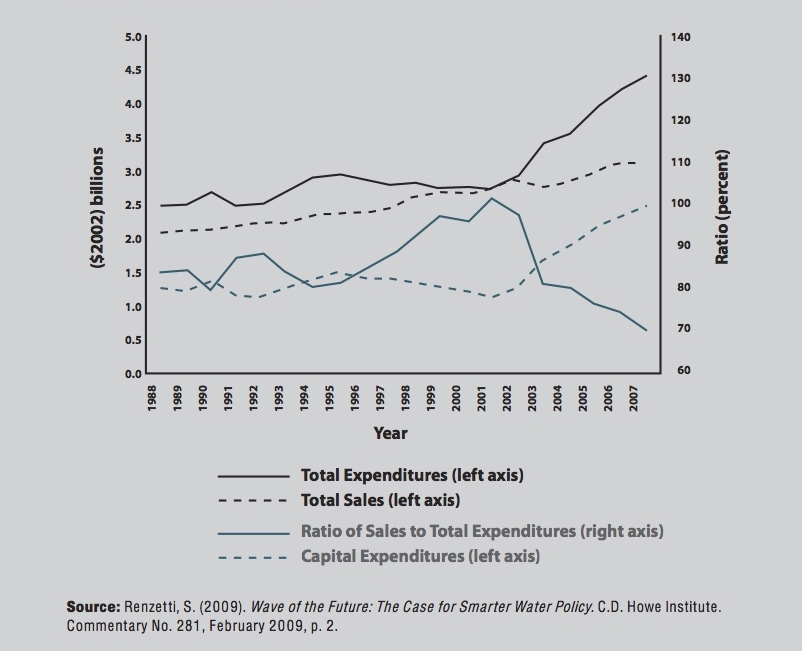

The outcomes from this model have not been favourable. Charging water rates that are less than the full cost of service has left municipal water budgets chronically underfunded, leaving a legacy of infrastructure deficits (see figure below). These deficits compromise the economic and environmental sustainability of water services. They leave municipalities with less money to pay for infrastructure upgrades and maintenance, and reduce their capacity to keep up with service upgrades, population growth, and extreme weather events. At the beginning of 2015, for example, at least 1838 drinking water advisories were issued in Canadian communities, many of which were caused by infrastructure problems.

Figure 1: Revenues and Expenditures of Canadian Municipal Water Agencies: 1988-2007

The takeaway here is that just because the full cost of municipal water services doesn’t show up on our water bills doesn’t mean the costs don’t exist. In fact, the opposite is true. Municipalities must make up the difference by drawing on property taxes, or borrowing money. Or, they can neglect the full cost of water systems, threatening access to clean water and risking even higher costs from contaminated drinking water or poorly managed watersheds.

Put your money where your value is

Canadians pay some of the lowest water rates in the world, but this isn’t because the costs of running water utilities in Canada are cheaper. Water and sewage systems are expensive to build, maintain, and operate. They are the biggest municipal asset—worth about $362 billion in Canada, or roughly 18% of national GDP. The City of Toronto’s network of water pipes, for example, is roughly 6,000 kilometres in length—roughly the distance from Victoria, B.C., to St. John’s, Newfoundland.

So, if water is so important, why aren’t we willing to pay the full price? Compared to most other essential goods (i.e. electricity, clothing, food, etc.) access to water is pretty cheap. On average, Canadians pay about $1 to $2 for every 1000 litres of water. It therefore seems odd that people aren’t willing to pay a little bit more if it means keeping our water systems in better shape.

Paying for what we use

Moving towards a user-pay model, where the full costs of service are included within our water bills, makes sense for several reasons. First, it gives water utilities the revenue they need to keep our water systems in a state of good repair. That also means they have the revenue stability needed to make important long-term decisions. Water infrastructure can last up to 100 years in the ground, so getting these decisions right is critical—especially when considering the challenges posed by climate change.

Second, a user-pay model can improve environmental outcomes. Paying a higher price for water sends a clear signal to waste less water. It also puts less strain on the natural ecosystems that support municipal water systems, and can lower operating and capital costs.

The application of user fees raises a host of important questions. By how much do water rates need to increase to ensure full-cost recovery? To what extent do people use less water if the price is higher? How will higher water prices affect low-income households and business competitiveness?

Here at the Ecofiscal Commission, we are working through these tricky issues. The RBC survey illustrates Canadians’ complicated relationship with water, and highlights the need for a wider conversation about how we pay for our water systems. Stay tuned for more on how municipal user fees—and paying the full cost of water services—can improve both economic and environmental outcomes.

Comments are closed.