Smooth sailing: Distance-travelled charges offer a flexible policy tool to tackle traffic

The topics of congestion pricing and tolling are heating up in a number of Canadian jurisdictions, most recently in Nova Scotia. We are taking the opportunity to shine a light on various forms of congestion pricing, based on our 2015 report We Can’t Get There From Here. This blog discusses distance-travelled charges, an approach that may just be the future of congestion pricing in Canada. But policymakers still face a key choice: is the goal to generate revenue or reduce traffic?

A versatile approach to pricing

Distance-travelled charges (DTCs) are exactly what they sound like: a mileage-based fee for vehicles. Unlike zone-based pricing, these fees are not limited to a specific series of roads. They offer greater coverage across a city or region. DTCs can apply to all vehicles, or target specific vehicle classes like heavy-duty trucks. Charges can vary based on time of use, route taken, direction of travel, distance, or any combination thereof. Mileage can be tracked in a number of ways, including low-tech methods like odometer counts all the way up to integrated GPS-based tracking. At the very least, the advancement of new tracking technologies means we can do away with tollbooths.

DTCs also open the door to more customized congestion pricing programs. The design should depend on the core objective.

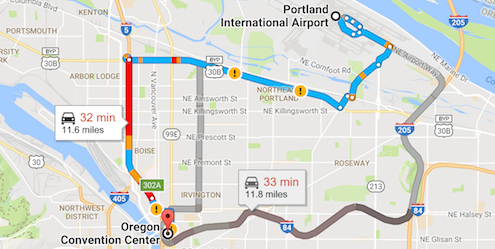

One option is to use variable or dynamic pricing to reduce traffic, either overall, or along specific routes at specific times. A system like this could work in Vancouver, a metro area with multiple hubs of activity, polycentric travel patterns, and a large number of bridges and tunnels. Variable or dynamic pricing could be used to reduce pinch points and improve the overall flow of traffic. The price per kilometre can rise or fall in real time to reflect the true costs of congestion at a given location, reducing traffic at the lowest overall cost.

Simple systems with static pricing, on the other hand, offer a stable, predictable source of revenue. They could, for example, address declining revenues from gas and fuel taxes. With the omnipresent demand for fuel economy and a growing number of policies designed to increase penetration of hybrid and electric vehicles on Canadian roads, distance-based charges can future-proof revenues against slowing demand growth for fuel. Adjusted to 2016 dollars, the federal gas tax generated $116 million less in 2016 relative to 1995, its year of inception. The federal Gas Tax Fund is directed largely to municipal infrastructure, so cities and commuters are the ones losing out here.

Several jurisdictions have implemented DTCs over the past decade. For a success story, look no farther than Oregon. This example also highlights the potential conflicts between generating revenue and reducing congestion.

Oregon original

In response to declining revenues, Oregon has piloted DTC programs to study their viability as a replacement for the state gas tax. The first 10-month pilot project launched in 2006 with the dual objectives of reducing congestion and revenue generation. Mileage was tracked with wireless GPSs.

The second pilot shifted the focus solely to revenue generation. It offered a basic plan, which reported only mileage, and an advanced plan, in which mileage and location were both tracked. Participants were billed 1.56 cents per mile (0.98 cents per kilometre) and received a fuel tax rebate in exchange. The revenue generated under this second program exceeded fuel tax rebates by almost 28%.

The most recent pilot, known as OReGO, launched in July 2015. This volunteer-based program applies to cars and light-duty commercial vehicles, and is currently limited to 5,000 participants. Drivers are billed 1.5 cents per mile driven. When their bills are issued, they receive a fuel tax credit.

The success of Oregon’s pilot programs suggests that DTCs can be designed to effectively reduce congestion or generate revenue, but there are some important trade-offs to consider. When combined with zone-based variable pricing, Oregon’s DTC resulted in a 22% decline in participant driving during peak travel periods. But reducing congestion comes at a cost. Revenues from variable pricing are inevitably less stable or certain, as it encourages people to change their driving behaviour.

Bumps in the road

Despite their flexibility and some real-world success, DTCs still face three significant hurdles: equity, privacy, and participation.

The equity argument tends to center on urban vs. suburban vs. rural. Rural dwellers tend to drive more and have access to fewer alternative modes of transport. The same argument holds in a weaker form for suburban dwellers. One solution is to offer a discounted rate for certain groups. But if a DTC is simply replacing other forms of revenue (such as a gas tax), then the problem is self-correcting. Heavy drivers will still pay the most; they will just pay through the DTC instead of through the gas tax.

Privacy is critical to obtaining public support. During Oregon’s first pilot project, drivers expressed reservations about sharing their information with the government. Programs that report mileage without GPS data can help allay these concerns, but also consign any DTC to a revenue tool instead of a congestion-reducer. Oregon’s program emphasized communicating the immediate, tangible benefits of the program to the public (i.e. gas tax rebates, real-time traffic data) to help assuage these doubts. Public buy-in would likely not have been possible without a targeted campaign to address privacy concerns.

Without this buy-in, transportation departments will be pressed to achieve widespread participation. Without widespread participation, DTCs will be less effective at reducing congestion, and program costs will consume a larger share of total revenue. Operating costs for a program with 10,000 vehicles would account for between 20% and 50% of the revenues, whereas a program with 1 million drivers would drive these costs down below 5%.

Go the distance

As new technologies emerge and our capacity to harness big data improves, the potential for DTCs in Canadian cities will continue to grow, especially in large, complex urban hubs like Metro Vancouver. And if Toronto revisits congestion pricing, DTCs would offer a more comprehensive and equitable option for reducing traffic than a flat $2 charge for the Gardner and the DVP.

As always, though, policy designers must be wary of multiple objectives. DTCs are proven, versatile tools capable of addressing multiple policy objectives, just not always at the same time.

Comments are closed.