Unpacking the WCI: Backhanded complements?

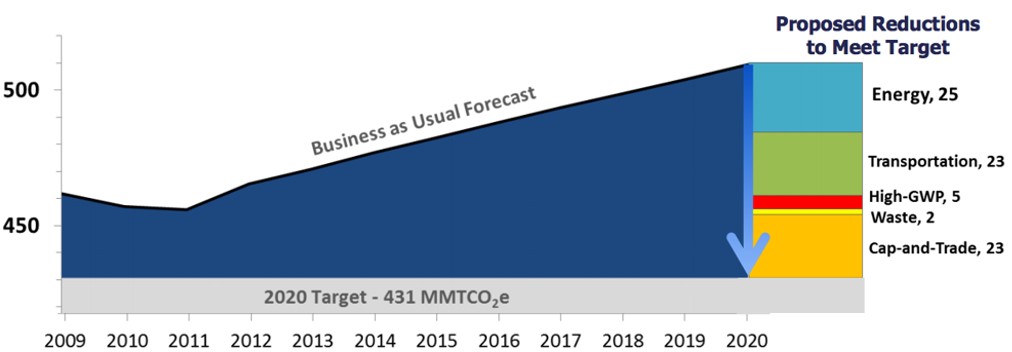

As we’ve noted in our summer blog series, California has a cap-and-trade system. But it’s also got a low-carbon fuel standard. And a renewable electricity portfolio standard. And vehicle emissions performance standards. And a swath of other policies to reduce GHG emissions. In fact, the California Air and Resources Board estimates that these “complementary climate policies” will contribute 70% of the emissions reductions required in 2020 in the state, as per the figure below. The cap-and-trade system is the backstop that will mop up the rest.

So let’s unpack one of the more hotly debated issues in cap-and-trade policy: are complementary policies in California a feature or a problem?

Interactions between cap-and-trade and complementary policies

As we’ve noted previously, interactions between policies complicate matters. The “cap” in California defines the total allowable emissions in the system: each emission produced requires a permit. But that means that other policies might not provide additional emissions reductions. Since the cap is fixed, fewer emissions from (for example) vehicles as a result of tailpipe regulation simply means that more emissions will come from some other source covered by the cap. Think of it like a balloon: you squeeze on one end, and the other bulges out.

Instead of reducing emissions, complementary policies can reduce the price of carbon in the cap-and-trade’s permit market. Lowering emissions through regulations and other policies means that emitters need fewer permits to comply with the cap. This then reduces demand for permits, causing the price to fall.

A tension between cost-effectiveness and acceptability?

So what does this effect on prices mean for policy (and for politics) in California? Here’s where opinions differ.

On one hand, complementary policies increase costs. Regulations might require more costly emissions reductions in place of cheaper ones. Check out this helpful explanation from Meredith Fowlie, economics professor at Berkeley. She writes, “right now, carbon markets are hamstrung by a growing medley / cacophony of policies that drive allowance prices down If we want to see carbon markets really work, we need to give them more work to do.” In other words, California is relying more on regulations than carbon pricing, increasing overall costs.

On the other hand, the lower price of carbon might be key for the public’s acceptance of cap-and-trade. Dallas Burtraw, economist at Resources for the Future, writes, “other companion policy approaches are necessary to achieve climate goals. Perhaps knowingly, the public consistently expresses a preference for regulatory approaches over emissions pricing.” In other words, regulations might be more costly, but those costs aren’t obvious to the general public in the same way that a carbon price is. In practice, complementary policies might make political space for cap-and-trade (and deeper reductions) by lowering the price of carbon.

Not all complementary policies are created equal

As usual, there’s room for compromise. Fowlie notes that there are good reasons for some complementary policies. And Burtraw suggests that “California has identified a fertile middle ground where both carbon pricing and companion measures contribute.” At the end of the day, sensible people generally agree that carbon pricing is important, but not the only piece of the policy puzzle.

The question then, is what separates “smart” complementary policies from… well, less-smart complementary policies? This is actually a tricky—though important—question, and is currently a key research issue for Ecofiscal. Smart complementary policies can help drive more emissions reductions at lower cost, can build constituencies for stronger policy, and can achieve other objectives. But badly designed complementary policies can increase overall costs unnecessarily. Stay tuned for more, as our analysis develops.

What about Ontario and Quebec?

Like California, Ontario and Quebec are part of the Western Climate Initiative, so face similar issues: Ontario and Quebec similarly plan to rely on complementary policies to help limit their emissions. There is, however, an important difference. California was the first WCI partner, and is still the largest in terms of emissions. For smaller players, like Ontario and Quebec, complementary policies are unlikely to affect prices. Instead, avoided emissions in Ontario or Quebec due to a complementary policy could simply lead to fewer permits imported from California. In other words, Ontario and Quebec’s complementary policies might lead to changes in permit flows rather than changes in permit prices.

We’re working on it

Complementary policies have a role to play in jurisdictions pricing carbon. Policy-makers across Canada are clearly considering policies ranging from methane regulations to coal phase-out to clean technology incentives. Ecofiscal doesn’t have all the answers yet, but stay tuned for guidance on this issue in future work.

Comments are closed.