Can incentives protect Canada’s clean water?

Clean water is a vital, valuable resource for Canada. We drink it. We grow food with it. We generate power using it. We use it as an input to industry, from manufacturing to oil and gas production. We swim, splash, and paddle our canoes in it. And clean water isn’t valuable just to humans; it also underpins essential ecosystems all over the country.

But do our policies reflect the importance of water? Sunday is World Water Day, and a good opportunity to think about ecofiscal implications for Canada’s water. A range of ecofiscal policies could help protect Canada’s clean water by harnessing market forces, though all have complications. We consider three broad policy categories below.

Municipal water usage fees

Let’s start with municipal user fees for water. Cities provide water to residents, but also treat wastewater. As Steven Renzetti, one of Canada’s preeminent water economists notes, Canadians generally pay much less than the costs of these services, and as a result, tend to overuse them. Well-designed user-fees—one element of the ecofiscal tool-kit—can help get prices right: the more residents pay for water infrastructure based on how much they use, the greater incentive they have to use less.

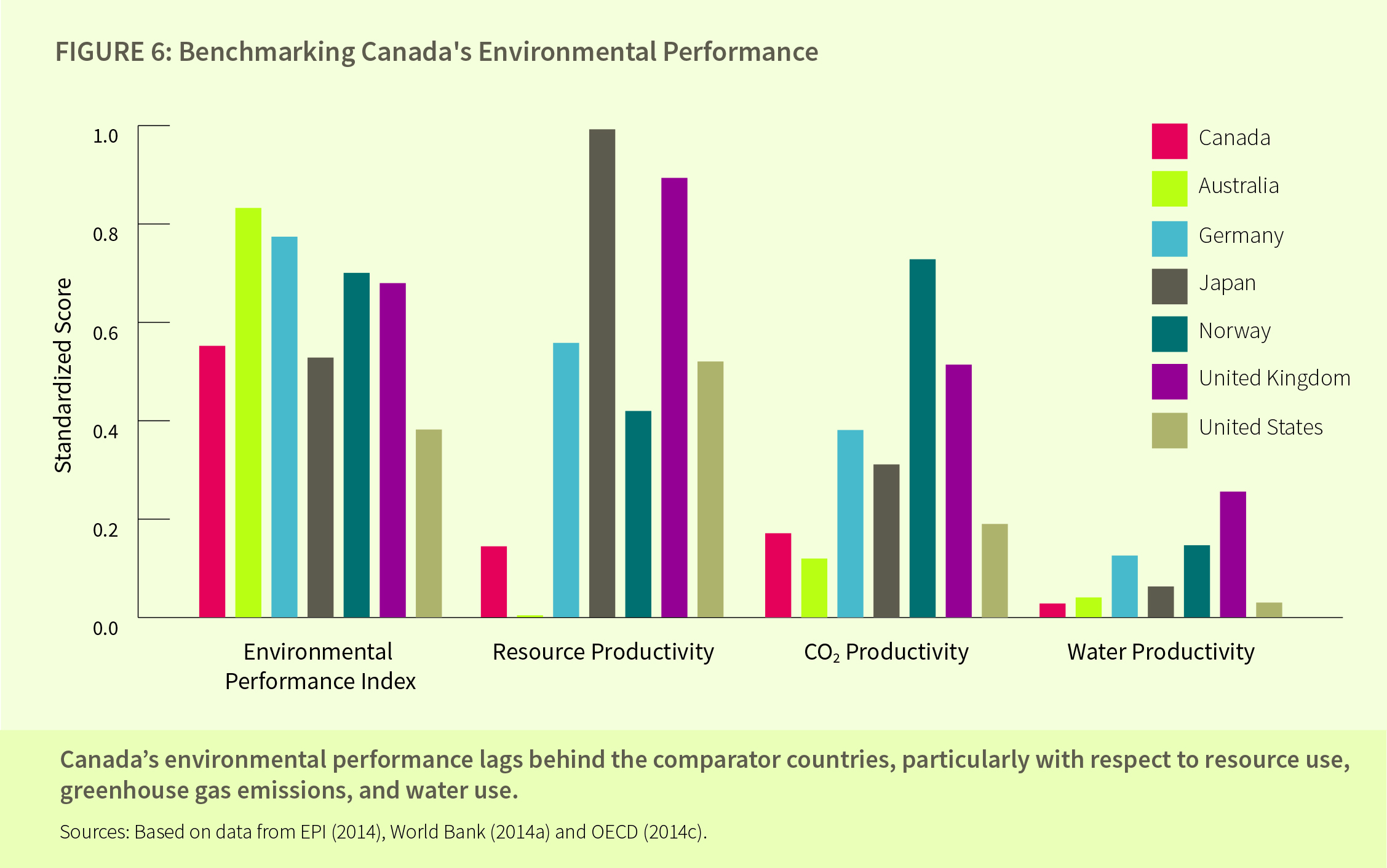

But it’s not just the infrastructure that has costs; the water itself has value. Depending on how water is used—for example for irrigation, or industry—water withdrawals have implications for ecosystems but also for the availability of water for other users. And if the price of water is too low, overconsumption can put stress on water supply. Currently, Canada uses more water per dollar of GDP (see Figure 6, from our Launch report, below) than other comparable countries. This stress matters in particular in regions of Canada where water supply under more pressure from factors like development and climate change. Water pricing can create incentives for conservation, but also ensure the resource is used in efficient way.

Protecting water from polluting effluent

Ecofiscal policies could also protect the quality of water by pricing effluent that pollutes fresh water bodies. Nutrient spillovers from agriculture, for example, have led to algal blooms in Lake Erie. Harmful effluents from mining operations can be toxic and threaten fish populations. Again, as a country, we can do better. Our relative wealth as a country in terms of clean water doesn’t mean that we don’t have a responsibility to manage these resources wisely. Smart policy can create incentives to reduce this pollution but also to innovate new, cleaner technologies.

Water pricing to create additional benefits

Like other ecofiscal policies, water pricing can also generate revenue that can be used to create additional benefits. User fees can generate new revenue streams for much-needed infrastructure. Abstraction or effluent pricing can generate revenue that can be used, for example, to reduce taxes, invest in water efficiency, or fund monitoring programs to reduce leaks.

That’s not to say there aren’t challenges. Water is essential to human life—some argue a fundamental human right—so any policy must ensure fair access to clean water. Others worry that putting a price on water is a commodification of a public good, leading to threats of bulk water exports to the United States. Technical challenges also exist. Water pollution often comes from a large number of small “non-point sources” that are hard to measure and track. And pollution can impose very different costs depending on where it is emitted in a watershed, potentially leading to different “optimal” prices of pollution for different emitters.

Yet smart policy can take these concerns into account, while harnessing market forces to better protect Canada’s clean water resources. Future work from the Commission will explore exactly these kinds of policy options in more detail.

Comments are closed.