TLDR: The skinny on Ecofiscal’s latest report about biofuel policies

The Ecofiscal Commission’s latest report, Course Correction, looks at the economic and environmental case for biofuel policies in Canada. If you don’t have time to read the report, here’s what you need to know.

Canadian governments have supported the production and use of biofuels for over two decades (see here for a quick intro to what biofuels are). On the supply side, governments have supported producers directly in the form of production subsidies (i.e. cash payments). On the demand side, the federal government and five provincial governments require fuel distributors to blend a minimum level of ethanol and biodiesel with gasoline and diesel, respectively.

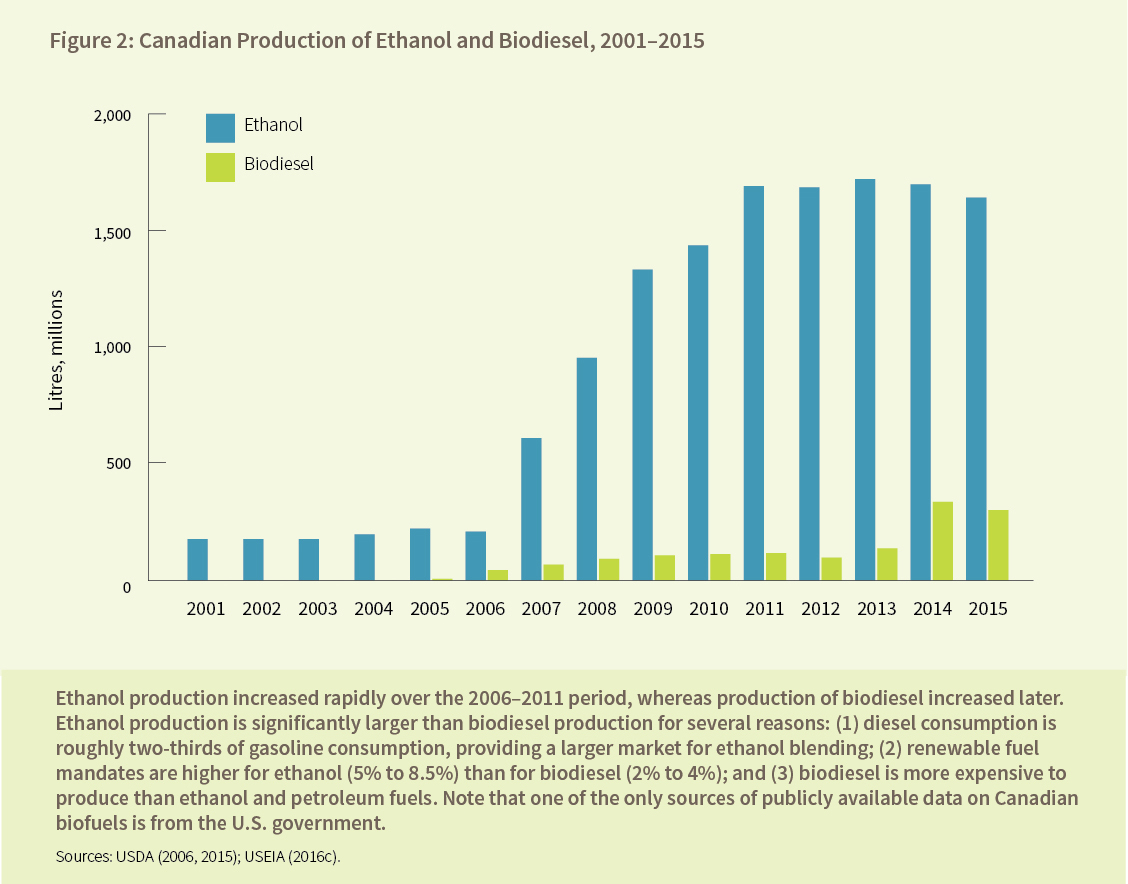

The combination of these policies have played an important role in expanding the production and use of biofuels (see figure below). Course Correction looks at the economic and environmental impact of these policies, including their effects on GHG emissions and overall costs to consumers, taxpayers, and the economy more broadly. We also compare these policies with alternatives that can reduce GHG emissions at a smaller economic cost, such as carbon pricing.

Biofuel policies are an expensive way to reduce GHG emissions

Biofuel policies were ramped up in the mid-2000s with the hope that biofuels would play a role in meeting emissions reduction targets. Our analysis shows that biofuels have indeed helped reduce GHG emissions. On average, biofuel policies have reduced emissions by roughly 3 Mt per year. This is equivalent to about 1.5% of Canada’s transportation emissions, or roughly 0.4% of the country’s total emissions.

But these emissions reductions have come at a high cost. When adjusting for energy content, biofuels are more expensive than fossil fuels, which means fuel mandates increase costs for fuel distributors and consumers. At the same time, production subsidies, which provide cash payments for every litre of biofuel produced, are financed by taxpayers. The combination of consumer and fiscal costs over the 2012-2015 period was about $640 million per year.

Whether you think $640 million is a lot of money, a good metric for comparing the cost of biofuel policies are the emissions reductions that have been achieved. We find that the cost of ethanol policies was about $180–$185 per tonne of GHGs reduced, and $128–$165 per tonne for biodiesel policies. That means that emissions reductions from biofuel policies are more than five times more expensive than emissions reductions from the carbon tax in British Columbia, at $30 per tonne.

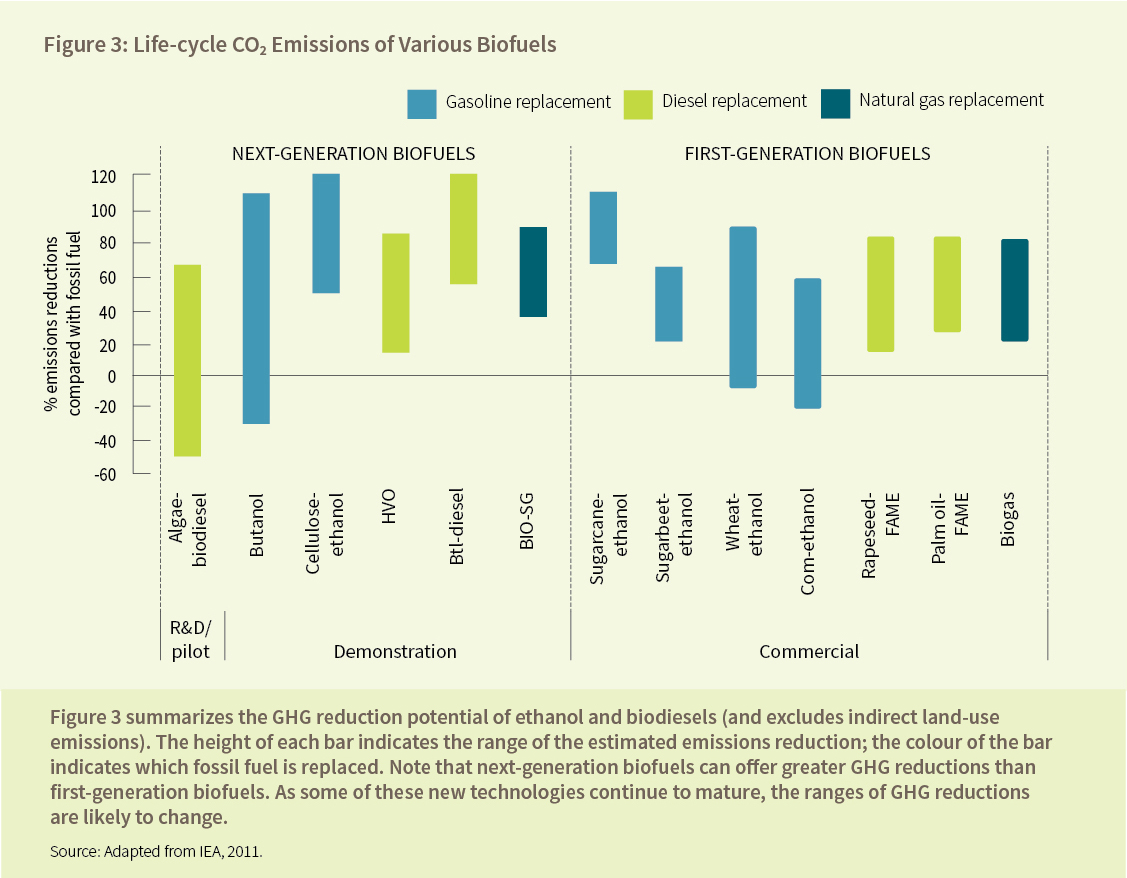

What is more, these estimates might be optimistic. The extent to which biofuels reduce GHG emissions is contentious due to the uncertainty around estimating the lifecycle emissions of biofuels (see IEA figure below). When we use less optimistic assumptions, the costs of ethanol policies increase to $238–$284 per tonne, and $189–$596 per tonne for biodiesel policies.

The other objectives of biofuel policies are unlikely to justify these high costs

Biofuel policies are an expensive way to reduce GHG emissions, but they were introduced to achieve other objectives as well. Governments hoped that biofuel policies would improve economic opportunities for farmers and rural communities, reduce air pollution, and accelerate the development of next-generation biofuels.

Overall, we find no conclusive evidence that these other objectives have been met. Biofuel policies may provide benefits to some Canadian farmers and biofuel producers, but these benefits are offset by adverse impacts on other farmers and other sectors of the economy. According to the federal government’s own cost-benefit analysis for its renewable fuel mandate, economic costs far exceeded benefits.

We also find that increased use of ethanol and biodiesel has had a negligible impact on reducing air pollution. This is partly because of the small blending levels of biofuels, but also because some biofuels can actually increase emissions of certain pollutants.

Finally, these policies have had little impact on the development and scaling up of next-generation biofuels. First-generation ethanol and biodiesel still account for nearly all biofuels produced in Canada. In addition, projections by the International Energy Agency suggest that biofuel production and consumption in Canada will remain flat in the short to medium term in the absence of new and effective government policies.

In with carbon pricing, out with biofuel policies

Based on our analysis, Course Correction makes four recommendations:

1. Provincial and federal production subsidies should be terminated, as initially planned. Production subsidies are scheduled to end in 2017-18. We argue that these policies should not be extended or renewed. Production subsidies are an expensive way to achieve emissions reductions. In addition, basic principles of subsidy design suggest that industry support should never last forever.

First-generation biofuels have now received more than two decades of substantial public support. If producing biofuels in Canada still proves uneconomic, there is a clear indication that additional support for the industry is not a good use of public money. The transition away from production subsidies will be assisted by the fact that firms benefiting from these subsidies knew from the outset that they would end in 2017-18, and could thus plan accordingly.

2. Provincial and federal governments should phase out renewable fuel mandates. Renewable fuel mandates will represent the biggest form of government support for biofuel policies once production subsidies end in 2017-18. As we’ve shown, these policies have been costly for consumers, who pay a premium when filling their tanks at fuelling stations.

Instead of providing equal incentives to any and all emerging technologies, existing renewable fuel mandates only benefit the biofuels sector—a subset of available and potential fuel technologies. And because higher-carbon biofuels (first-generation) are typically cheaper and more readily available than lower-carbon biofuels, renewable fuel mandates send a weak incentive for next-generation biofuels and no incentive whatsoever for other vehicle or fuel technologies.

Yet, there is value in having a smooth policy transition. Renewable fuel mandates have provided stable demand for the biofuels industry, a relatively small group of producers and farmers. Policies should therefore be gradually phased out over the span of several years to ensure that industry has sufficient time to adjust. Most importantly, the final two recommendations will help ensure that clear incentives still exist for low-carbon transportation technologies, including biofuels.

3. Provincial and federal governments should continue to work toward an increasing pan-Canadian carbon price. This recommendation, perhaps unsurprisingly, follows from the other work at Ecofiscal which argues that carbon pricing is the most effective and cost-effective way to achieve Canada’s climate targets.

The emergence of carbon pricing in Canada is changing the landscape for climate policy; we argue that targeted biofuel policies are no longer necessary. Achieving a broad-based carbon price in Canada will shift the incentives for developing and deploying low-carbon technologies by increasing the value of technologies—including some biofuels—that can deliver more GHG emissions reductions at a lower cost.

The Ecofiscal Commission therefore continues to support Canadian governments in their pursuit of establishing carbon pricing as the best overall policy tool to achieve Canada’s climate targets.

4. As part of the policy transition, governments should complement carbon pricing with flexible performance standards and broad funding for research and development. By itself, a pan-Canadian price on carbon may not be enough to meet Canada’s emissions-reduction targets. Market barriers may make it particularly difficult to reduce transportation emissions. Few alternatives to fossil fuels exist and infrastructure requirements can create barriers to the deployment of new technologies.

To make the shift to low-carbon transportation, provincial and federal governments should replace renewable fuel mandates with flexible performance standards. Low-carbon fuel standards, for example, can offer a cost-effective approach to transitioning to new technologies—extending incentives beyond biofuels to other low-carbon fuels. Other flexible performance standards, such as zero-emission vehicle standards, should also be considered as valuable complementary policies. As governments implement broad carbon prices that increase in stringency over time, the flexible performance standards should be gradually phased out.

In addition to introducing flexible performance standards, provincial and federal governments should continue to fund research and development of low-carbon transportation technologies. This will help complement a pan-Canadian carbon price and flexible performance standards by bridging the gaps between discovering, testing, and scaling up new technologies that are currently too costly for private firms to pursue or deploy.

Read the Report Check out our Events

Comments are closed.