Stormy fees: Stormwater user fees can reduce flooding risk and improve municipal finances

Ecofiscal’s latest report assesses how well-designed user fees for municipal water and wastewater services promote conservation, generate revenue, and improve water quality. The report, however, scoped out the third pillar of municipal water systems—stormwater services. This blog fills the gap by looking more closely at stormwater services and how user fees can reduce flooding risk and improve municipal bottom lines. For a concrete example we look westward, at Victoria’s new stormwater user fee.

Stormed out

Municipalities would be a soggy mess if it weren’t for stormwater systems. Runoff from rain and snow that would otherwise accumulate is collected in underground storm sewers and through dispersed networks of culverts, ponds, and other pieces of green infrastructure that act like natural sponges. These systems are the first line of defence against urban flooding, especially as municipalities densify and cover more cityscape in asphalt and concrete. They also help manage the quality of stormwater, which helps protect the health and safety of residents.

Like other types of municipal infrastructure, however, stormwater infrastructure across Canada is aging and requires significant investment in coming decades. By one estimate, the national funding deficit for stormwater infrastructure in poor or very poor condition was $10 billion in 2016.

That’s probably a conservative estimate. It doesn’t include future costs, particularly in growing communities that will require more expansive and expensive infrastructure. Nor does it include the future infrastructure costs required to lessen the impacts from more frequent and severe flooding from climate change.

Adapting to these new realities will be costly. But not having adequate infrastructure may be costlier still. Recent floods in Calgary and Toronto resulted in over $7 billion in damages, mostly from basement flooding. More flooding also means more untreated sewage and stormwater going into our waterways, or worse, mixing with flood waters in urban environments.

Paying the way with user fees

How can municipalities ensure they have adequate stormwater infrastructure to minimize flooding risk (and costs to residents) without breaking the bank? The answer may lie in how we pay for these services.

Most Canadians pay for stormwater infrastructure through their property taxes, just like other municipal services, such as road maintenance and snow removal. This funding model, however, has drawbacks. The amount paid in taxes has no clear connection with the volume of runoff from each property. Properties with low volumes of runoff end up subsidizing properties with high runoff volumes (e.g., parking lots, big driveways, etc.).

Relying exclusively on property taxes can also exacerbate funding shortfalls. Infrastructure investments compete with other municipal expenditures, making it difficult to secure stable and adequate funding.

Instead, municipalities across North America are implementing stormwater user fees. Under this funding model, residents pay, in part, based on the amount of runoff from their property. This approximates each properties’ “use” of the stormwater system, typically based on the amount of impervious (hard) surfaces on each property. In doing so, it provides a continuous incentive for property owners to reduce runoff, which reduces flood risk. User fees can also generate predictable revenues, helping municipalities plan and pay for much needed infrastructure.

To illustrate the benefits of stormwater user fees, we look to the City of Victoria, nestled on Vancouver Island’s rainy southern coast.

Stormwater fees on Canada’s wet coast: Victoria, B.C.

Stormwater services in Victoria were historically financed through property taxes. But like other cities, Victoria faces a considerable infrastructure gap for its stormwater infrastructure. The city’s 2014 master capital plan contained a robust plan for infrastructure renewal, but had no clear way to pay for it. The coastal city also expects climate change to increase flooding risk in the future.

To deal with these challenges, the city of Victoria replaced its property-tax model with stormwater user fees in 2016. In doing so, it created a separate stormwater utility exclusively responsible for planning, financing, and operating the system.

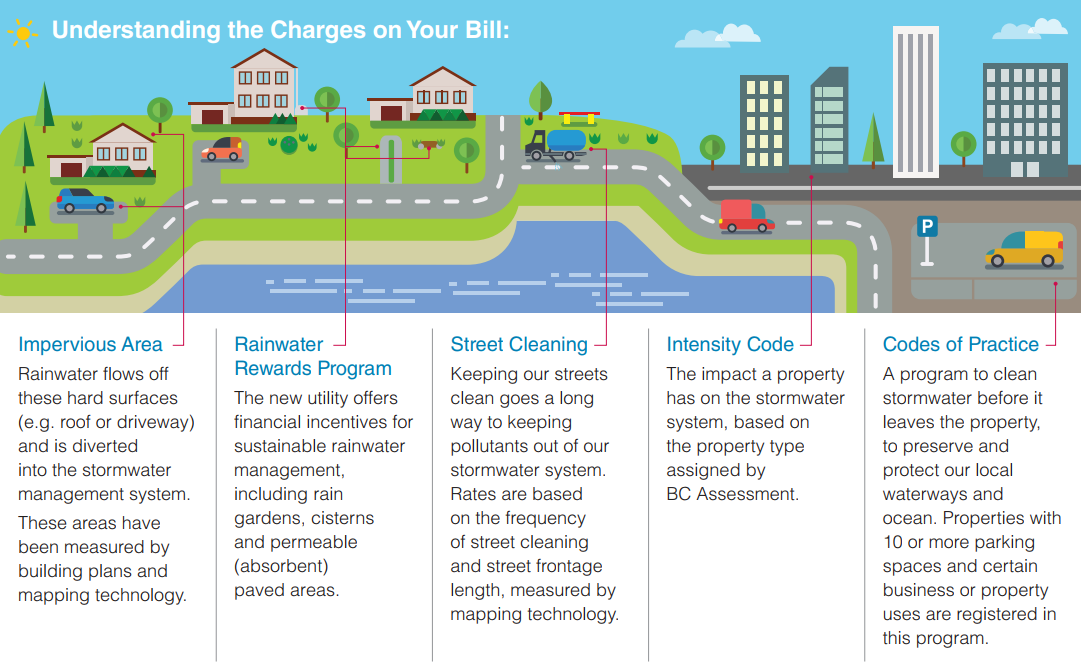

Victoria’s stormwater fees are based on several factors, illustrated in the figure above. Generally, rates are based on: impervious surface area on each property, street cleaning services, and building type. Some properties with large parking lots pay an additional fixed fee to help clean stormwater before it leaves the property. And a rewards program helps offset the cost of installing rainwater management technologies, such as rain barrels and rain gardens.

Lessons from Vic

Victoria’s stormwater user fee is still new, but several lessons are noteworthy.

Risk Reduction. The city’s variable fee for impervious surfaces provides a continuous incentive for property owners to reduce runoff. The rewards program for rainwater technologies makes these improvements even more attractive. Over time, these incentives for reducing runoff should reduce flooding risk for property owners and the municipality as a whole.

Cost-effectiveness. Victoria’s stormwater user fee aligns the costs of the system with those who use it most, which improves cost-effectiveness. In other words, the city is reducing flooding risks at a lower cost: the net cost to the average property owner is expected to be neutral through a reduction in property taxes. According to city staff, this was a big factor in garnering support.

Revenue Stability. Creating a separate stormwater utility helps create stable and predictable funding for the city’s stormwater system. Further, the fixed portion of the stormwater fee provides predictable revenues. This helps provide stability if revenues from the variable rate decline as property owners reduce runoff from their properties.

Timing. The transition to a user-fee model was gradual. The city council green-lighted a preliminary study in 2009, and officially endorsed the idea in 2011. After considerable research and analysis by city staff, the by-law was drafted and adopted in 2014. Implementation was delayed until 2016 to ensure the city (and residents) were ready for the transition.

Implementation. The eventual roll-out of user fees was met with relatively minor opposition. The city conducted extensive public engagement and made a concerted effort to highlight the fairness of user fees: properties that generate less runoff should pay less.

Lessons for all municipalities

Over twenty municipalities in Canada have transitioned to stormwater user fees, with more on the horizon. If designed well, they can reduce flooding risk and minimize costs for taxpayers. They’re also flexible and can be implemented in different ways, with varying degrees of complexity, catered to each municipality’s unique context.

So, while stormwater user fees didn’t make it into our municipal water and wastewater report, it’s a powerful and increasingly popular tool in the municipal toolkit.

Comments are closed.