Canada’s park paradox

Canada’s national parks host millions and millions of visitors every year, and entry was free in 2017 as part of Canada 150. As you might expect, people have flocked in record numbers. But national parks belong to the public. Should access always be free? And aren’t more visitors, rather than fewer, a good thing? In this blog, I’ll discuss why this may not be the case.

Trampled under foot

Canada’s national parks system consists of 327,000 km2 of protected land — about half the size of Alberta, or 3.3% of our total land mass. When we include other subnational parks and privately protected land, it’s 10.5% of Canada’s land mass.

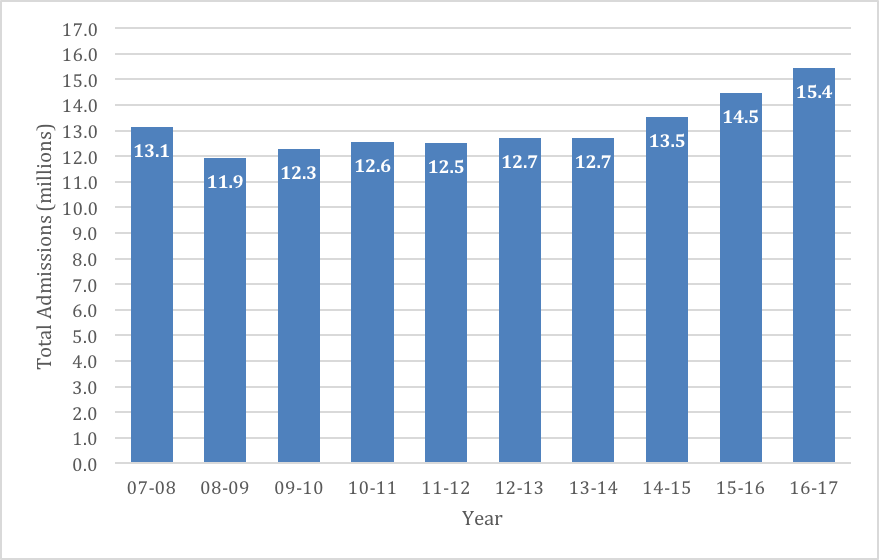

Canada’s national parks were free to access in 2017. In the first half of the year, overall attendance was up by 12%. In some parks, year-over-year attendance has spiked by 20% or 30%. That is a lot of extra bodies. In one case, a park had to shut down due to overcrowding. Too many people at once, or too many people overall, can mean a host of environmental issues, ranging from litter to noise pollution.

Figure 1: National Park Attendance in Canada

Source: Parks Canada

Park Paradox

Our parks serve competing objectives. On one hand, they are there for Canadians to appreciate and connect with nature. On the other, we want to keep them pristine, so they receive special protections from development. We’re allowed in, but some activities are off-limits; a compromise of sorts.

Why is that?

A few costs come with entering and enjoying a park. One is the environmental footprint, however slight, of anyone who goes off-trail or off-road, or doesn’t pick up their trash, or gets a bit too cozy with wildlife. Another less obvious cost is tied to the fact every park has a capacity. When you enter a park, you prevent someone else from being able to enter, no matter how much they may want to or how much they’re willing to pay.

User fees make sense for our parks and protected areas for two main reasons:

- First, that price signal helps maximize the value of those natural resources. Even a nominal price can screen out anyone who doesn’t necessarily value the space, but would be willing to access it for free. Their reluctance to pay keeps park attendance at healthier levels, helping to preserve the space.

- Second, the nature lovers who enter and enjoy our parks —and pay the fee— will directly fund conservation and stewardship efforts.

Both groups are contributing to the park’s long-term health, one through their absence, one through their pocketbook.

The next question is, of course, how much?

The price is right

We want to both conserve and ensure access to our parks. How do we preserve them for the next generation and keep them affordable (for everyone, not just the wealthy)?

Parks could charge, and charge a lot, which ensures conservation but undermines affordability. It’s also not certain it would even increase revenues, since fewer people would visit overall. Charging high fees will limit our environmental footprint, but will put access out of reach for many. This criticism has been levelled at the U.S., who in October announced plans to double admission fees in some of its national parks.

Parks could be free, but that creates the opposite problem. This approach ensures access, but may compromise conservation.

For anyone, but not for everyone

Charging a nominal entry fee for our parks makes environmental and economic sense. It signals the value of nature to visitors, generates revenues for upkeep, and ensures accessibility. And there are different ways to charge. Some parks use what’s called variable pricing, where visitors pay different amounts depending on what time of the year (or even the day) that they enter the park. This approach can help reduce attendance during peak times. Another option is dynamic pricing, where the price changes in real time depending on the number of people currently in the park.

Everyone values nature a little differently. By charging a price for our national parks, we can ensure that only people who value nature will pay to access it and help fund its preservation; those who don’t, won’t. The user should pay, and every Canadian should have the chance to be a user. In other words, we want anybody to be able to access our parks, we just don’t want everybody to.

Comments are closed.