An explainer on the federal carbon pricing backstop

Yesterday, the federal government announced the details of its carbon pricing “back-stop.” The plan lays out an approach to filling the gaps across Canada in provinces that aren’t implementing their own carbon pricing policies. It also considers the net impacts on people in those provinces. The upshot? The system is a simple, transparent approach to putting a price on carbon across Canada.

How did we get here?

OK, let me take a step back. As regular Ecofiscal readers will know, in 2017 provincial governments across the country and in partnership with the federal government agreed to put a price on carbon as part of the “Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change.”

That choice was a sensible one. Economists—including those here at Ecofiscal—agree that carbon pricing works. It’s cost-effective, and can reduce GHG emissions at lower cost than any other policy option. It can drive clean innovation.

Further, the system accommodated provincial differences: it built on success in provinces already moving forward with carbon pricing, and gave other provinces the flexibility to design their own systems, while ensuring that revenue would not be generated in one province and spent in another.

Since then, however, we’ve seen a few provinces back away from carbon pricing. The backstop released is designed to fill the gaps. It ensures we have a carbon price across the country. And that coordination is a good way to minimize the costsof reducing GHG emissions in the country as a whole.

Where will the backstop apply?

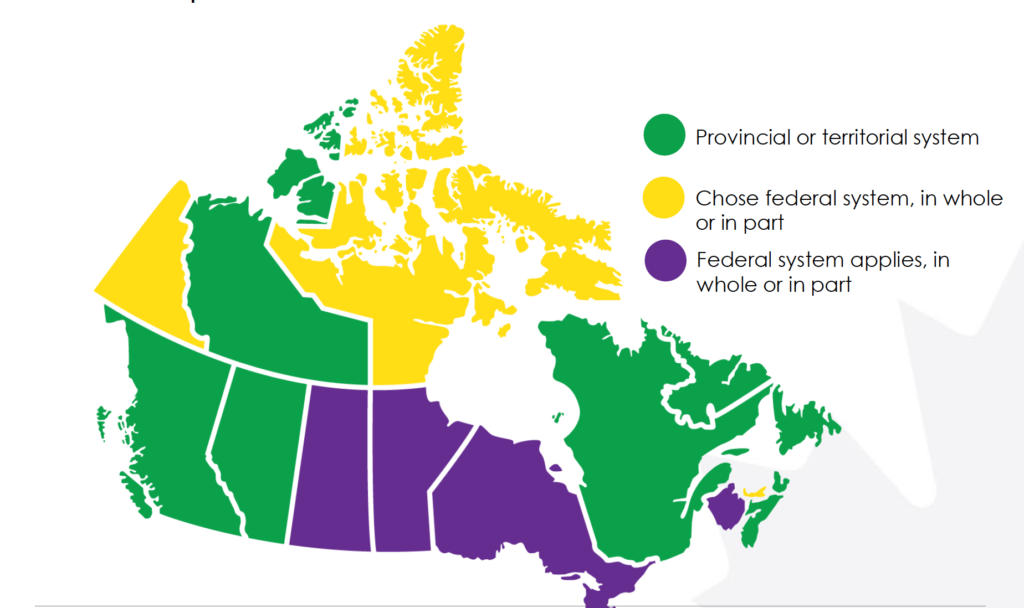

The announcement identifies the provinces that will see the federal backstop (whether whole or in part), as per the figure below.

For me, there are two main takeaways here:

First, we’ll see the federal backstop imposed in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and New Brunswick. Each of those provinces will have revenue returned to their citizens, not their provincial governments (more on that in a second).

Second, we should expect more policy details soon from Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador. All of those provinces have avoided the federal backstop, despite some outstanding questions about how their systems will work.

Who benefits from revenue recycling?

Maybe the biggest news today is about revenue recycling. The announcement shows how revenue generated by the carbon price in backstop provinces and territories will be recycled back to households in those jurisdictions.

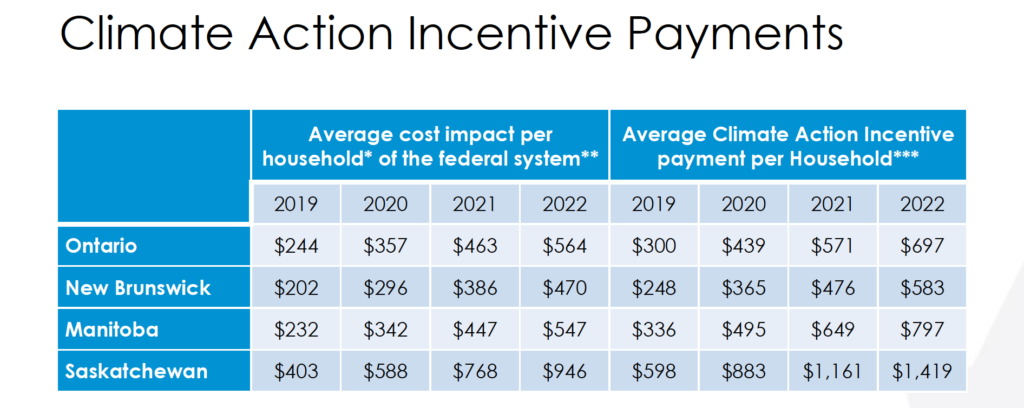

Ninety percent of that revenue will go to families in the form of a “Climate Action Incentive” payment (or in plain language, a rebate cheque). Larger families get a bigger rebate. Rural families get a slightly bigger rebate. And for the average family (70% of households) the rebate will more than offset the costs of carbon. The table below is based on documentation from the federal government.

Critically, these rebates do not undermine the incentive to reduce GHG emissions. Everyone gets a rebate. But people can further reduce their costs by taking actions to reduce their emissions and avoid paying the carbon price. And that’s exactly the point.

The remaining 10% of revenue will be used to provide support for municipalities, universities, schools, hospitals, indigenous communities, and small and medium-sized businesses.

What about small businesses and competitiveness?

It’s worth unpacking that support for small and medium businesses. Is it big enough? Does it address concerns around the competitiveness of these firms? For three reasons, sending the money to households, rather than those small and medium businesses, can make sense.

First, in most cases, those businesses will ultimately pass on their carbon costs to consumers (i.e., households) anyway. Ultimately, households will see most of the costs from carbon pricing, so it makes sense that they also see the benefits of revenue recycling.

Second, the broader issue of industry competitiveness has already been addressed through the other carbon pricing policy that prices emissions for large emitters (and smaller emitters that choose to opt-in) through an “output-based” approach.This system makes sure that industry has incentive to reduce GHG emissions by improving their performance, not by shifting production (and emissions) to other jurisdictions.

Third, we should be viewing competitiveness through a broader lens than carbon pricing anyway. Carbon pricing is only one factor affecting business competitiveness, and a relatively small one at that. Another key factor is corporate tax rates. And notably, small business taxes rates in Canada were lowered earlier this year to 10% and will be lowered again in January to 9%. That’s the lowest rate in the G7 and 4th lowest in the OECD.

What about other options for revenue recycling?

All revenue recycling choices have trade-offs, including giving rebates to households. Some economists might still prefer revenue used to cut other taxes. Some environmentalists might prefer to use the money to fund clean technology. But those doors are still open: moving forward, provinces could implement their own policies in the future, avoid the federal backstop, and use revenue as they see fit.

What’s next?

Here’s the bottom line: the carbon pricing backstop is a simple, transparent mechanism that returns all revenue generated in a province back to citizens in that province. It puts a price on carbon across the country. Will we need higher carbon prices over time? Absolutely. But this is a great start.

2 comments

I’ll admit off the hop that all this climate change stuff, politics and economics is above my pay grade but please explain how taking my money in the form of a tax and then giving it back to me in the form of a rebate does anything to help save the planet. Something here doesn’t add up.

Thanks for the question, Sandy. Here’s another blog explainer: https://ecofiscal.ca/2018/09/26/how-carbon-dividends-affect-incentives/

Bottom line, the rebate doesn’t depend on how much carbon you produce, but the costs of the carbon price does. So if you don’t change your behaviour, you come out roughly even. If you do change, you come out ahead.

Comments are closed.